|

|

ETCHED BEADS

The art of bead etching most probably began in the Indus Valley Civilization.

Indians were the first to etch beads with soda, and from

there the art spread along the trade routes to other

countries. Etching was accomplished by applying an

alkali, usually a soda or plant ash solution, and heat

to the stone surface. This would cause the stone to

become discolored or frosted in appearance, creating the

design. The process required precise control of the

chemical application and heating process, and the

artisans of the Indus Valley were skilled at it.

These etched beads from the Indus Valley civilization

have been found not only in the Indus region itself but

also at sites across the ancient world, from Mesopotamia

to Central Asia and Egypt. This suggests that they were

highly valued trade goods, and their spread helped to

disseminate the bead etching technique to other

cultures.

Displayed below you can see etched Indus Valley beads from Pakistan.

|

The beads in

my collection

are now for sale

Inquire

through bead ID

for price

|

|

|

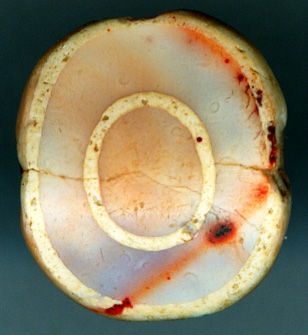

EB 0 - 13 * 11 * 5 mm

- SOLD

|

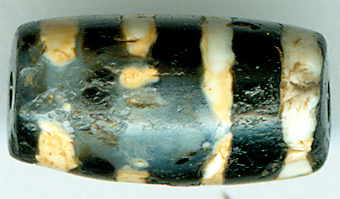

EB 3 -

12 * 4,5 mm - SOLD

This bead is actually not etched,

but displays natural lines in

jasper stone.

|

|

The wonderful etched eye bead to the left is designed in the rare double ax form. This design is even older than the designs from the Indus Valley culture. They can

in West Asia be dated back to the Neolithic period.

LINES, CONTRAST, PATTERN, AND SHAPE

|

|

|

|

EB 1 - 12,5 * 4,9 mm

|

In evaluating the artistic and

historical significance of etched beads, there are several key aspects

to consider.

Line quality

The precision, delicacy, and uniformity of the etched lines can tell us

a lot about the skills of the artisans who made the beads. The thickness

of the patterns, especially in well-preserved beads, can be indicative

of high quality craftsmanship, as seen in some of the ball beads you

mentioned.

Contrast

The contrast between the etched design and the underlying color of the

bead material is another important factor. A high degree of contrast not

only enhances the visual impact of the bead but also demonstrates the

bead maker's mastery of the etching process, which involves carefully

controlled application of alkalis and heat.

Pattern uniqueness

The rarity and distinctiveness of the etched patterns can significantly

increase the artistic and historical value of the bead. A bead might

have a perfectly executed but common design, or it might have a unique

and unexpected pattern that sets it apart, like the bead with the rare

variation on the typical cruciform. Such designs offer unique insights

into the cultural and symbolic world of the people who created and wore

these beads.

Bead shape

Lastly, the overall shape and form of the bead itself is an important

consideration. The shape can often be linked to specific cultural

preferences or symbolic meanings. For instance, the bead with a

perfectly oval shape and a flat backside is an intriguing example of the

variety of forms produced by ancient bead makers.

The analysis of these factors together provides a comprehensive

evaluation of the aesthetic and cultural significance of etched beads.

It also reveals the expertise and creativity of the ancient artisans who

created these enduring works of art.

Ancient, but never used |

|

|

|

Taxila,

Pakistan?

EB 2

15 * 13 * 4,5 mm |

|

|

This distinctive flattened oval bead

indeed presents a fascinating case study in bead history. Despite its

pristine condition, which led some observers to initially suspect it

might be a modern creation, the presence of iron oxide within the etched

lines on the backside of the bead provides compelling evidence of its

ancient origin. The penetration of iron oxide into these etched lines is

a slow process that takes an extended period, commonly referred to as

'geological time'. This supports the hypothesis that the bead is indeed

ancient.

Additionally, the bead's rich patina, likely a result of prolonged

burial, provides further corroborative evidence of its antiquity. Its

apparent unused condition suggests that it might have been a burial

casket bead, intended for ritual use rather than everyday wear.

The bead's relatively small hole, in contrast to the larger holes

typically found in the ball beads from the same period, might hint at an

evolution in bead-making techniques or aesthetic preferences over time.

It suggests that the bead could date from the later stages of the

Greater Buddhist India period.

In terms of its design, the complexity of the etched pattern seems to

mirror the trend in the evolution of Buddhist symbology, such as the

mudras or symbolic hand gestures of the Buddha. As Buddhism evolved and

spread, the

language of these symbols became increasingly intricate and nuanced,

a development that seems to be mirrored in the bead's intricate design.

In sum, this bead provides valuable insights into the artistry, ritual

practices, and cultural evolution of its era. It highlights the

importance of careful analysis in bead study, illustrating how even

seemingly contradictory features can come together to tell a complex and

intriguing story of the past.

|

|

|

|

EB 3 - 16 * 8 mm - SOLD

|

|

|

|

EB 4 - 14,5 * 8 mm - SOLD

|

|

Black decoration

Beads

adorned with black etchings are significantly rarer,

marking a unique and intricate process in their

creation. In this particular method, the entire bead

initially undergoes a soda treatment. This step turns

the surface of the bead white, as seen in the examples

of EB 20 & 21. Subsequently, the desired patterns are

etched onto this blank, white canvas.

However, the etching in this case is not performed with

soda. Instead, a solution of iron or manganese compounds

is employed, which imparts a black hue to the etched

designs, standing out distinctly against the white

surface of the bead. This process, though

labor-intensive, results in strikingly beautiful and

distinctive beads, lending a rare quality to the pieces.

This technique is discussed in detail in S. B. Deo's

work, 'Indian Beads'.

|

|

|

EB -

11 * 6,5 mm

- SOLD

|

EB -

11 * 7 mm - SOLD

|

|

|

|

|

EcthedIndus 1 - 19 * 8 mm SOLD

Zoom in

|

|

|

|

EB 26 -

29 * 15 mm

(Brm 28)

|

|

|

|

EB 29 -

21 * 10 mm

|

EB 30 -

19 * 7 mm |

|

|

|

EB 31 -

18,5 * 4,5 * 8 mm

|

EB 32 -

17 * 5 mm

- SOLD |

|

|

|

EB 33 - 16,5 * 7 mm |

EB 34 -

15 * 7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

EB 35 -

15 * 7 mm

|

EB

36 - 14 * 6,5 mm |

|

|

|

EB 37 - 14 * 7 mm

- SOLD

|

EB 38 - 14 * 7 mm

- SOLD |

|

|

|

EB

39 - 13 * 5 mm

|

EB 40 - 15 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

EB 41 -

13 * 8 mm

|

EB 42 -

12 * 8 mm |

|

|

|

EB 43 -

11 * 5,5 mm

|

EB 44 - 10 * 4 mm |

|

|

|

EB 45 - 10 * 4 mm

|

EB 46 - 6 * 5 mm |

|

|

|

EB 47 - 5 * 4 mm

|

|

|

|

|

EB 22 -

14 * 7,5 mm

- SOLD

|

EB 23 -

14 * 7 mm

- SOLD |

|

|

|

EB 24 -

12 * 6,7 mm

- SOLD

|

EB 25 -

13 * 5 mm

- SOLD |

|

|

|

EB 48 -

15 * 9 mm

|

|

The bead displayed above was sourced from

Burma. It has a typical Burma pattern. However it could be found anywhere within the ancient Buddhist kingdom of greater India.

Beads are great travellers.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

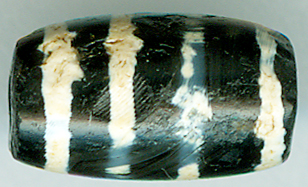

Above 3 etched beads from Burma with typical Burma

design

|

|

|

|

EB 52 -

14 * 7 mm

- SOLD

|

EB 53 -

17 * 7 mm |

|

|

|

EB 54 - 11 * 6 mm |

EB 55

- 10 * 6

mm

|

|

|

|

EB 56 -

8 * 4 mm -SOLD

|

EB 57 - 7 * 6 mm

-SOLD |

|

|

|

EB 58 -

10 * 7 * 4 mm - SOLD

|

|

|

|

|

EB 59 -

5 mm

|

|

|

Most probably the small white dots were made to serve as protective eyes. Ancient beads were used, not only as decoration,

but as amulets.

Sourced from Nepal.

DIFFERENT ETCHINGS REFLECTS DIFFERENT SOCIAL STRATA IN SOCIETY

The beads shown below

offer a glimpse into the different social strata of

ancient societies, as reflected through the quality and

intricacy of bead etching. A spectrum of etched beads is

presented, ranging from medium quality to the simplest

forms. Each bead's intricacy, design, and execution can

potentially tell a tale of the owner's social standing,

starting from the sophisticated bead on the left and

concluding with the group of simpler beads displayed in

the final photo.

The exquisite Swastika bead, EB1 likely belonged to an

individual of high social status or wealth. Its

meticulous etching, intricate design, and superior

quality materials signify a high level of craftsmanship,

typically accessible only to the elite. Such beads would

have been coveted status symbols, signifying power,

prestige, or wealth.

As displayed below, the beads become increasingly

less intricate and less carefully executed. These

may have belonged to the middle strata of society -

individuals who had enough resources to afford

decorative beads, but not the finest ones. The designs

on these beads are simpler, but they still represent a

form of personal adornment and status.

Finally, the group of beads at the bottom represents the

most basic level of etched beads. These beads are the

simplest in terms of design and craftsmanship. The

etchings are rudimentary, and the overall execution

lacks the refinement seen in the higher-quality

examples. These beads may have been accessible to the

broadest swathe of society, including those of lower

social status.

This gradation of bead quality and intricacy likely

mirrored the stratification of society, offering a

tangible and enduring record of the social dynamics of

the time. Each bead, regardless of its quality or

intricacy, served as an expression of personal identity

and social standing. As such, they offer invaluable

insights into the past, reflecting not only the

aesthetic preferences of the period but also the

socio-economic structures of these ancient societies.

|

|

|

|

EB 67 -

11 * 7 mm - SOLD

|

|

|

|

EB 68 -

7 mm

|

EB 69 -

6mm |

|

|

|

EB 70 - 7,5

mm

- SOLD TO HERVE |

EB 70 -

10 mm

|

|

|

|

EB 71 -

15 * 7 mm

- SOLD TO HERVE

|

EB 72 -

13 * 6 mm - SOLD |

|

|

|

EB 73 - SOLD

|

|

|

ETCHED BURMESE BEADS

You will find the etched Pumtek Beads

on this link. They are

so typically Burmese that I chose to display them on the

Burmese Beads page.

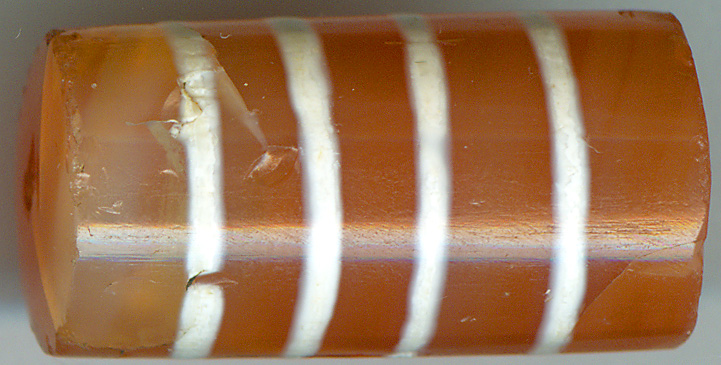

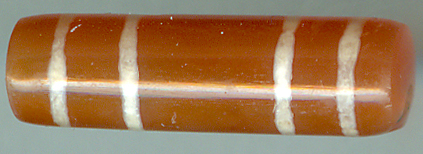

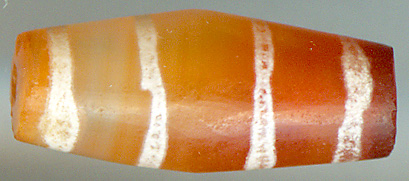

Military beads?

This ancient carnelian Pyu bead has been colored by oil, gas, and pressure.

You can read more about it here. On the

internet, these kinds of beads are presented as military beads. I find it odd that a peaceful Buddhist culture like the Pyu's would have so many beads with military symbols. Stripes on beads, especially carnelian beads, are found everywhere in Greater India. The stripes most probably indicate animistic magic properties in a Buddhist context. However, particular this bead is typical for Burma and not for India.

|

|

|

|

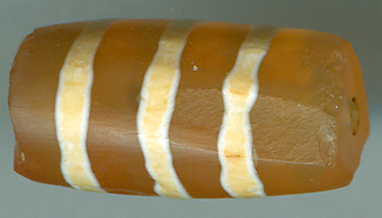

Etched Carnelian with 4 stripes

EBB

76

-

29 * 15 m

|

|

|

|

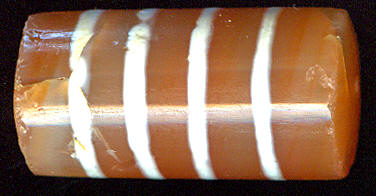

Etched Carnelian with 5 stripes

EBB

77

-

31 * 11 mm

|

Most probably many of these etched carnelian beads have traveled between India and Burma with Buddhist monks and traders more than 1000 years ago. They were found in Matehtilay, Maline.

Burma embraced Theravadan Buddhism, influenced from Thailand around 1050. These artifacts, however, show the strong and direct Indian cultural influence during the times of the Pyu City states from 200 B.C. to around 1000 A.D.

|

|

|

|

Striped Burmese Ball Beads

|

|

|

|

EBB

80

-

15 mm

|

|

|

|

EBB

82

-

9,5 mm

|

EBB

83

-

9 mm

|

|

|

|

EBB

84

-

10 mm

|

EBB

85

-

10 m

|

|

|

|

EBB

86

-

8,3 mm

|

|

|

|

|

EBB

88

-

7,5 mm

|

EBB

89

-

10 mm

|

|

|

|

EBB

90

-

8 mm

|

EBB

91

-

8 mm |

|

|

|

EBB

92

-

7 mm

|

EBB

93

-

8 mm |

|

|

|

EBB

94

-

10 mm

|

EBB

95

-

7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

EBB

96

-

8,5 mm

|

EBB

97

-

7,5 mm |

|

|

|

EBB

98

-

9 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

|

EBB

100

-

Upper: 21 * 10 mm

Click on picture for larger image

|

|

|

|

EBB

101

-

13 * 3,5 mm

|

EBB

102

-

11 mm

|

NEW ETCHING ON OLD BEADS

Here you can observe a primitive etching on beads with poorly crafted forms. I showed the photo of these beads to some expert bead hunters in Burma. They called these beads 'village beads'. They said that they in their bead hunting had observed a great difference between beads found in ancient city areas and in village areas. It seems that the custom of poor people copying the finer crafted rich man's city beads in these more crude forms was widespread.

|

|

|

|

Largest bead upper left: 11 mm

|

Nowadays one has to be extremely careful when purchasing etched beads.

One of the etched beads displayed above is most probably a fake. The bead itself is old, but the etching is new. Can you identify the bead?

Here are some more examples of new etchings made on old beads:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

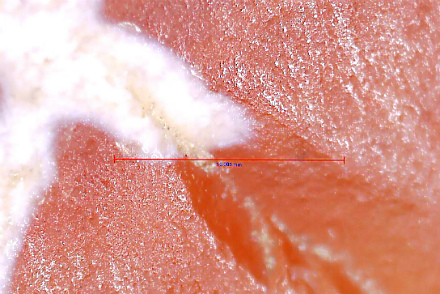

As a general rule

new etchings are thin, almost transparent, as one can clearly see in the beads above. Often one can observe how the new etching follows the old marks in the beads in a way that it would not do if the etching was as old as the bead itself. Note the way how the etching follows the crack in the lower left corner of the bead displayed below.

If the etching is as old as the bead itself, the lines would have disappeared

in there areas where later small damages occur, as you can see in the bead below:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| | | |