|

|

BEADS FROM BURMA

The range of styles and types of beads showcased on this

page is a testament to the mastery and advanced

techniques employed by Burmese bead artisans. Over the

past five years, browsing through various bead websites,

I've observed a peculiar trend: all beads from Burma

have been relabeled as 'Pyu/Tircul' beads. This is, in

fact, an oversimplification.

Without a doubt, the

Pyu/Tircul culture played a

significant role in bead making in Burma, yet bead

crafting also flourished in various other regions and

periods within Burma. Referring to all Burmese beads as Pyu/Tircul beads disregards the fact that a substantial

exchange of beads transpired between India and Burma,

driven by trade and shared Buddhist cultural ties.

It's plausible that this oversimplification has occurred

to make it easier to market and sell Burmese beads to a

burgeoning middle-class audience, primarily in the East,

who may not be as invested in the deeper, more complex

historical and cultural nuances.

PUMTEK DZI BEADS

Featured above is a bead discovered among many in a

ruin in rural Punjab, India, near the Pakistani border.

These beads, likely burial beads or at least never used,

display

slight discoloration from the surrounding earth. How

they ended up in this remote location far from Burma

remains a captivating bead-mystery.

In Memory of my Friend, Professor Bhandari

These unique beads were found by my dear friend,

Professor Bhandari, during his lifelong quest for

ancient coins throughout India. Now no longer with us,

Mr. Bhandari was an ardent collector of ancient coins.

His expeditions frequently led him to beads as well,

often retrieved by young boys living near archaeological

sites who earned some extra money from visiting

collectors like Professor Bhandari.

Professor Bhandari's coin hunting season invariably

commenced after the monsoon season, when the rain had

eroded the soil, facilitating fresh discoveries. It was

the Professor's modest collection of beads, which he

kindly gifted to me, that kindled my passion for bead

collecting. |

The beads in

my collection

are now for sale

Inquire

through bead ID

for price

|

|

|

These ball beads below were sourced from the Bagan area.

They are high-quality antique production beads from the early 20th

century. |

|

|

|

Brm

2

-

Largest ball bead: 15 mm

|

Pumtek

beads, also known as buried

thunderbolt beads, hold significant cultural

importance among the Chin people living in the Chin

Hills of western Burma/Myanmar and the adjacent area of

eastern India, where they are referred to as Kuki. The

original Pumtek beads were crafted over a millennium ago

by the Pyu, the founders of the earliest city-states in

Burma. Intriguingly, the art of Pumtek bead making

managed to survive in the mountainous regions, far

removed from the fertile rice plains of Bagan during its

zenith.

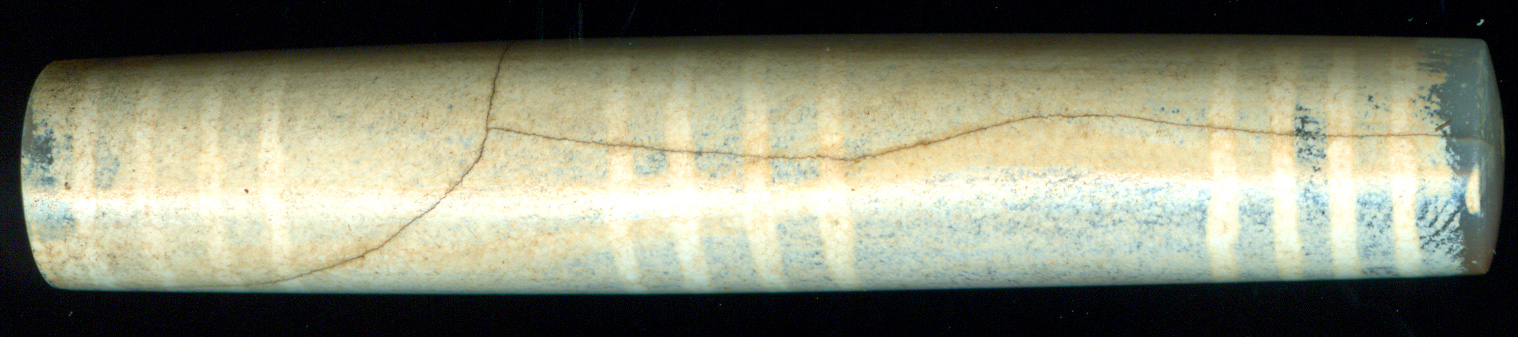

Ancient Pumtek beads are often quite small, typically

crafted from the opalized wood of the Borassus

flabellifer palm. These specific types of beads will

fluoresce when exposed to a short-wave UV lamp.

However, not all Pumtek beads are made from opalized

palm wood. Many are created from different types of

petrified wood, often in the form of chalcedony, and

despite this variation, they can still be quite ancient.

Petrified wood, derived from a wide variety of trees,

can be found all over Burma. It's only natural that

ancient bead makers, as well as their contemporary

counterparts, have opted for this striking material. As

demonstrated in the above photo, the original form and

structure of the wood are preserved in the form of a

woody grain.

There are a lot of different varieties

of petrified wood in Burma. (Museum in Mandalay)

Many Burmese beads are made of petrified wood.

OLD PUMTEK BEADS FROM THE CHIN CULTURE

|

|

|

|

Brm 3

-

Small Chin Pumtek ball beads - 5,5 mm

|

The petite Pumtek beads featured here originate from the Chin State,

crafted with remarkable precision and intricate detail. The individual

who provided me with these artifacts specified that these are not

original Pyu beads. Instead, they are Chin replicas, estimated to have

been crafted approximately 500 years ago.

According to this source, the tradition of crafting these original

Pumtek beads from the Pyu city-states has been perpetuated within the

Chin community for the past millennium. The sustained production of

these beads over such a vast span of time illustrates the enduring

cultural significance and revered craftsmanship these pieces represent.

Even as "copies", these Chin-made beads embody the fusion of rich

heritage, timeless aesthetics, and the masterful technique of beadwork.

These beads, although not directly from the Pyu period, are steeped in

the same tradition and craftsmanship, and continue to be tangible ties

to a rich and complex history.

Elongated small Pyu beads

|

|

|

|

Brm 4

-

Largest 24 * 6 mm

|

Small rectangular Chin-Pumtek beads

|

|

|

|

Brm 5

-

12 * 10 * 5 mm - average size

|

|

Wonderful ancient beads from Burma

|

|

|

|

Brm 6 - 47 * 9,5 mm

- Click on picture for larger image

|

|

|

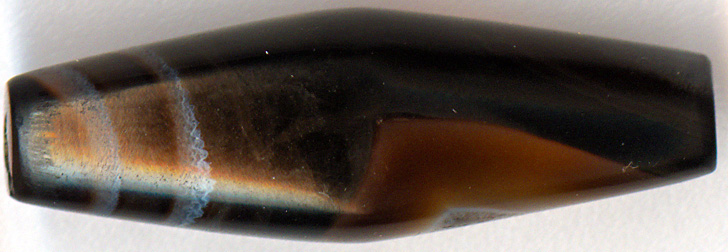

Pyu repair-bead

This ancient Pyu bead has been 'repaired' by cutting off the ends of the bead. The repair itself seems to be quite old.

|

|

|

|

Brm 10 - 15 * 14 * 5 mm

-

SOLD

|

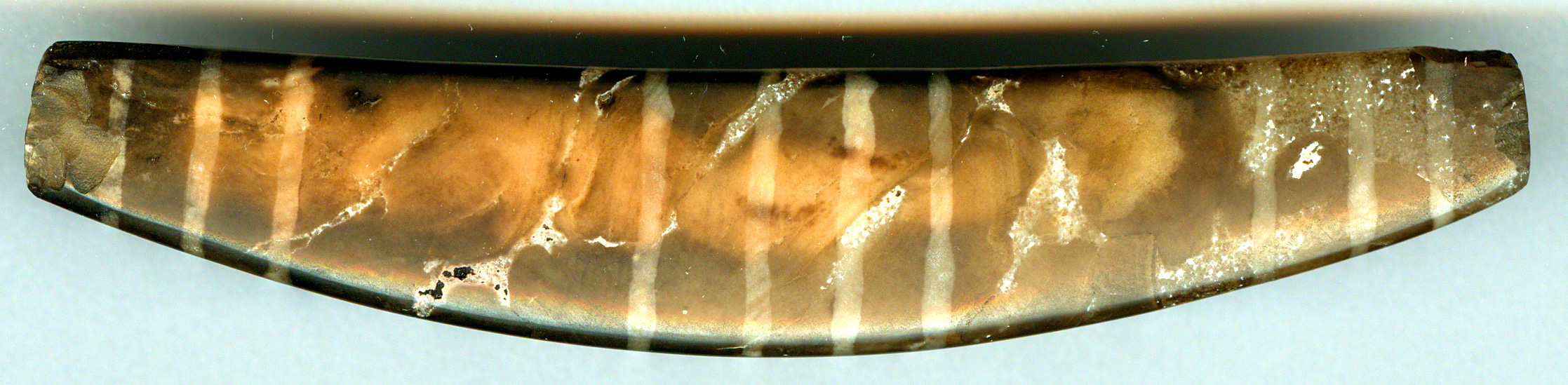

Large, rare & wonderful ceramic Pyu bow Bead

|

|

|

|

Brm 11

- 91 * 17 * 5,5 mm

Click on picture for larger image

|

|

|

|

20 * 20 * 5 mm

30 * 30 * 5 mm 17 * 17 * 3 mm

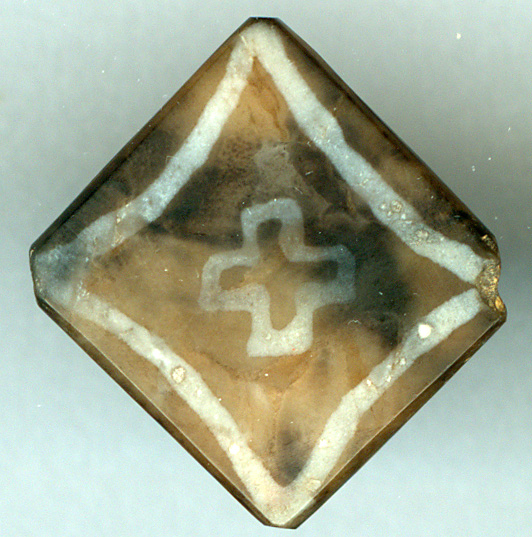

Square ceramic beads with the typical Buddhist cruciform pattern.

Brm 12 Brm 13 Brm 14

|

Ancient Tibetan DZI?

The bead, steeped in intrigue and mystique, is

purported to be an extremely ancient form of Tibetan DZI

bead. When I presented it to a Tibetan expert dealer

specializing in DZI beads in Kathmandu, he believed

ibelowt to be a powerful talisman with the ability to

prevent stroke and brain hemorrhage. The bead's striking

feature is its multitude of 'eyes', a typical

characteristic of DZI beads believed to provide

protection and auspiciousness to its owner.

However, its age and authenticity have sparked some

debate. Several other experts I have consulted have cast

doubts about the bead's antiquity. Thus, while it

carries a certain appeal and folklore attached to it,

definitive conclusions about its age and origin remain

elusive.

|

|

|

|

Brm 15

- 61 * 12 mm

Click on picture for larger image

|

|

|

|

|

ELONGATED TRANSLUCENT CARNELIAN BEADS

|

|

|

|

Brm 22 -

Largest bead 57 * 8,5 mm

NO 4. FROM THE RIGHT

IS

SOLD

|

|

|

|

Brm 23 - Upper: 49 * 6 mm

|

|

|

|

Brm

24

|

Bow beads - carnelian and agate

|

|

|

|

Brm 25

-

Click on picture for larger image

|

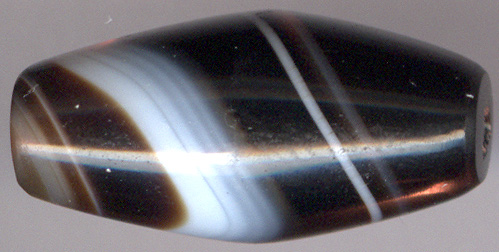

ETCHED BURMESE BEADS

In this

section, I showcase a selection from my collection of

Burmese etched beads, each bearing unique and distinct

characteristics. Notably, the collection features a

splendid large Jasper bead adorned with white stripes

arranged in 3, 5, and 3 formations. These white stripes

lend an intriguing visual depth to the bead, seemingly

not just etched, but carefully carved into its red

Jasper surface. This exquisite piece offers a stunning

testament to the artistry and attention to detail that

have been characteristic of Burmese bead craftsmanship

over centuries. Despite only featuring a few from my

collection here, each piece encapsulates the rich

cultural and historical heritage of bead-making in

Burma. |

|

|

Etched 12 striped carnelian bead with earth-oil patina |

|

|

|

EBB

75

- 63 * 10,5 mm -

Click on picture for larger image

|

Military Beads?

Displayed here is an ancient carnelian Pyu bead, its distinctive

coloration a result of exposure to oil, gas, and pressure. It's

intriguing to note that such beads are often identified as 'military

beads' on the internet, a label that seems rather incongruous

considering the Pyu culture's Buddhist pacifistic leanings.

Stripes on beads, particularly evident on carnelian ones, are a common

feature across Greater India. Rather than bearing a military

connotation, these stripes likely originated as imitations of natural

banded agate stripes, intended to convey animistic magical properties

within an animist context. However, it should be noted that this

specific bead, with its unique characteristics, is more typical of Burma

than of India.

Long & shorter

Truncated Convex Bicone beads

|

|

|

|

ClMatehtilay, Maline, Burma

| |

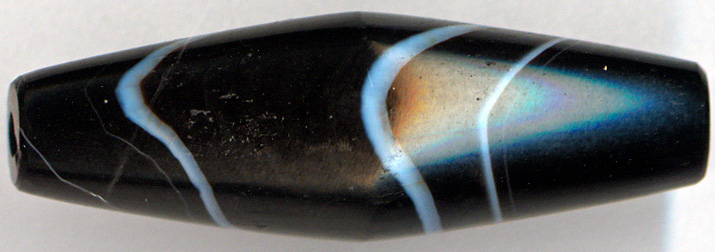

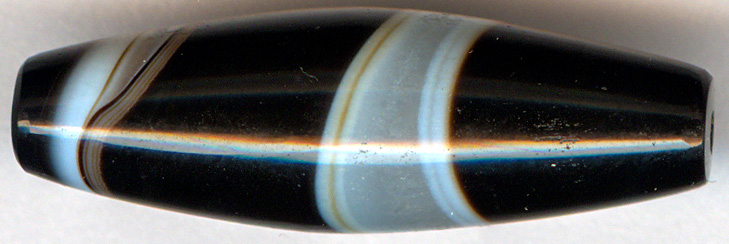

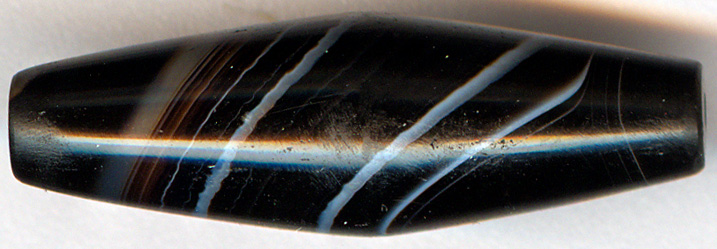

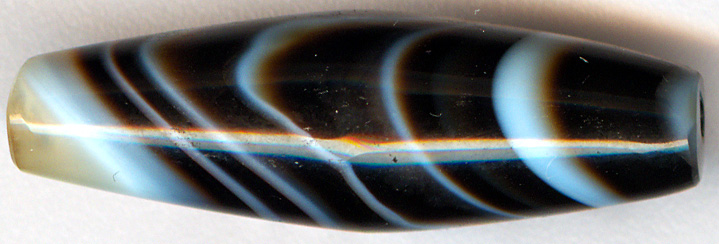

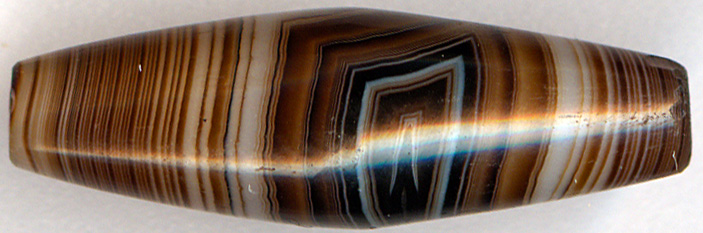

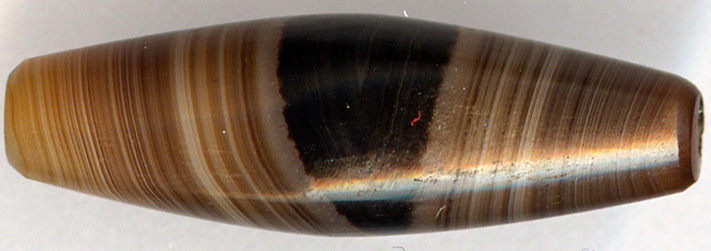

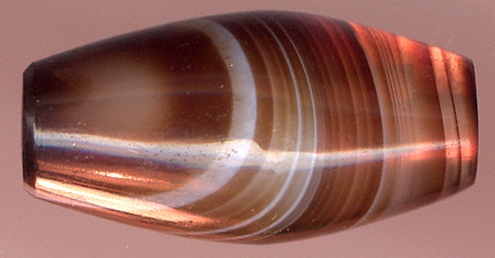

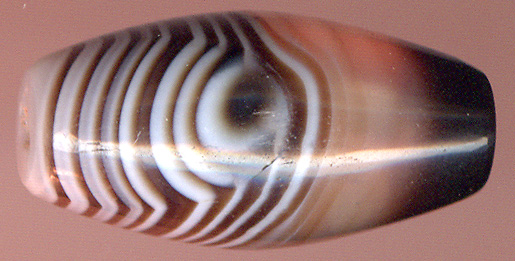

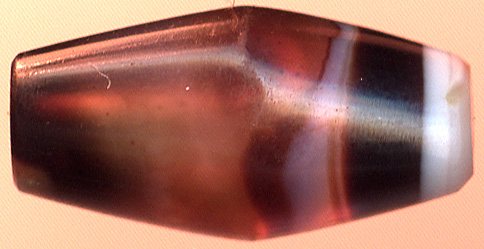

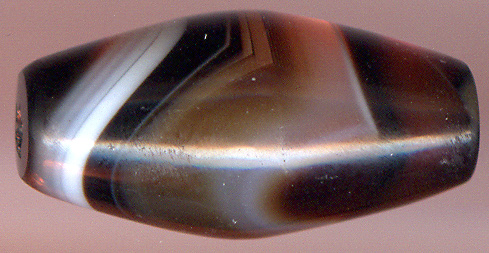

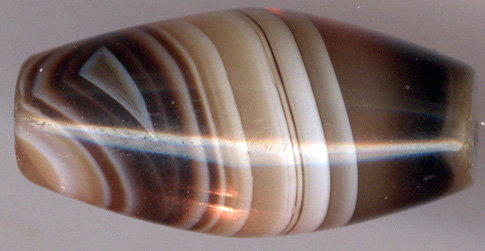

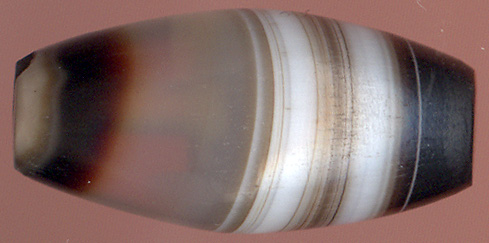

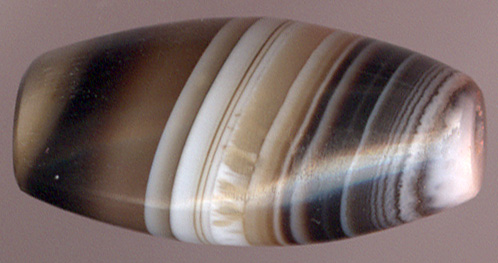

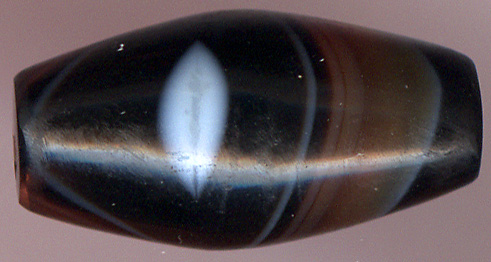

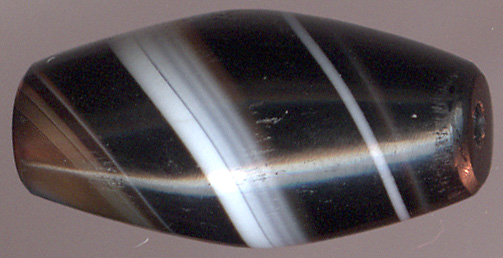

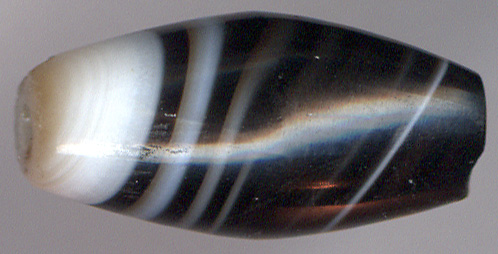

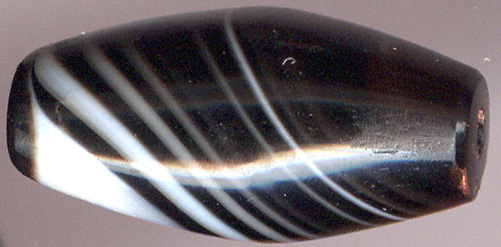

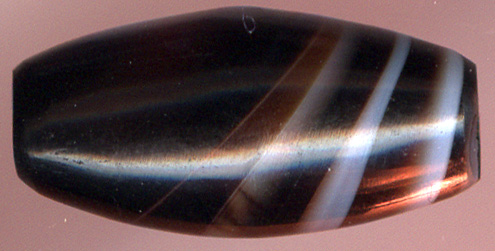

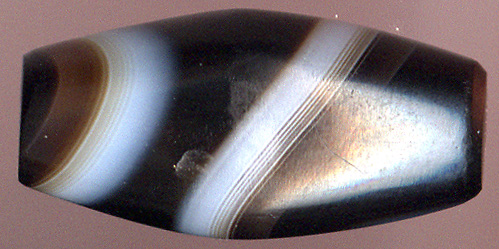

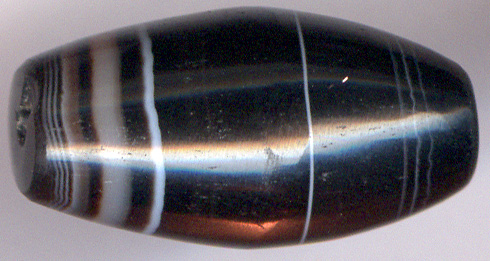

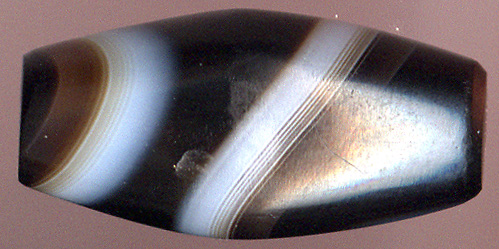

These exceptionally beautiful Sulemani beads

look like new beads.

I have not seen such colors, in a play of black

translucent stone and banding as one can observe in

these beads. They are all hand-polished and

oil cooked.

The shine of the many of the beads still have oily

reflection colors.

A close examination of the holes and the surface of the

beads shows that they have not been used. However, they

are ancient, displaying the most wonderful excavation

patina with a lovely soft sheen. They have been stored away as precious

jewels in

a long forgotten and destroyed burial site or they have been put in a

Buddhist

relic casket from and old Stupa.

You can read

more about excavation beads here. I marvel at this ancient skill of letting the artful patterns emerge out of the raw stone.

These beads are most probably a product of Burma's own craftsmen.

30 * 10 mm

Origin: Burma

I have singled this bead out of the lot because of its exceptional beauty.

|

|

|

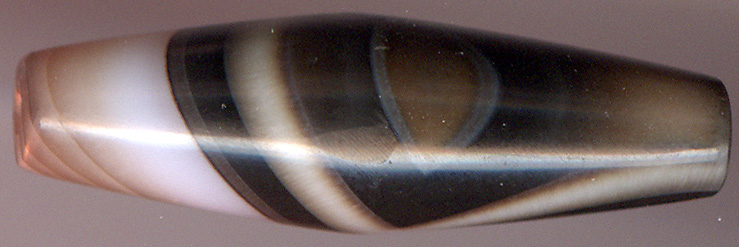

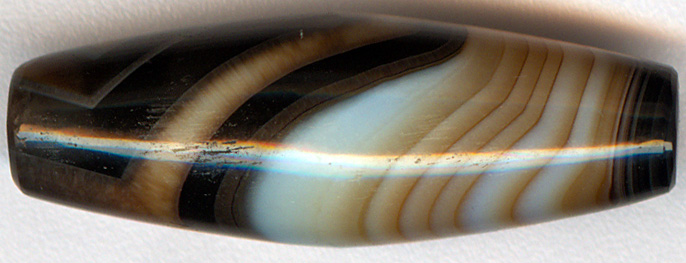

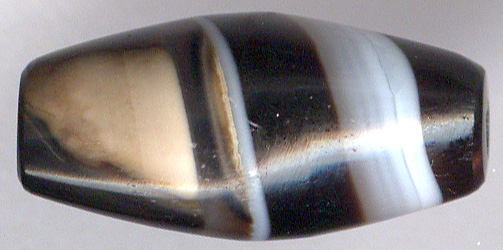

In this assortment

of Buddhist Burmese beads, we find a broad spectrum of

patterns and colors. From black onyx adorned with white

stripes to more traditional translucent agate beads with

swirling motifs in various hues, the diversity is truly

remarkable. You can compare the black onyx bead SM 142

with SM 156, for instance.

The uniqueness of these beads is underscored by the fact

that similar examples can only be found on a site

featuring

beads from Bangladesh.

Ancient beads from

Mahastan, Bangladesh.

Note the apparent similarity to

bead no. 4 in the first row

Please note that the

images above most accurately depict the beads' colors in

natural daylight. In the series of images below, I've

endeavored to showcase the beads' translucent nature

through the use of a secondary light source.

|

|

|

|

Brm -

SM 142 (2) - 30 * 10 mm

Click on pictures for larger image |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 143 - 29 * 9,5 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 144 - 30 * 9,5 mm

- SOLD TO HERVE |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 145 - 28 * 9,5 mm

- SOLD TO HERVE |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 146 -

|

| |

|

Brm -

SM 147 - 29 * 9 mm

|

| |

|

Brm -

SM 148 - 29 * 9,5 mm

|

| |

|

Brm -

SM 149 - 28 * 9 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 150 - 30 * 9,5 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 151 - 29 * 9 mm

|

| |

|

Brm -

SM 152 - 29 * 9 mm

|

| |

|

Brm -

SM 153 - 29,5 * 9,5 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 154 - 29 * 10 mm

|

| |

|

Brm -

SM 155 - 29,5 * 10 mm

- SOLD TO HERVE

|

| |

|

Brm -

SM 156 -

Click on pictures for larger image

|

| |

|

Brm -

SM 157 - 20 * 10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 158 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 159 - 19 * 10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 160 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 161 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 162 - 19,5 * 10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 163 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 164 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 165 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 166 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 167 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 168 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 169 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 170 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 171 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 172 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 173 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 174 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 175 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 176 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 177 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 178 - 20 * 10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 179 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 180 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 181 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 182 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 183 - 19,5 *10 mm |

| |

|

Brm -

SM 184 - 19,5 *10 mm |

|

Burmese Glass beads

|

|

|

Down left: 24 * 14 * 7 mm

Brm - glass 1

Click on picture for larger image

|

|

These Pyu glass beads are made in resemblance of the typical Burmese jade.

|

|

|

|

Colourful glass beads

from the

Mon Dynasty

16 * 5,5 mm

Brm - glass 2

Click on picture for larger image

|

Burmese Nagaland glass beads

These wonderful blue glass beads are from the Burmese part of

Naga Land. They are around 100 years of age, made in India as copies of the much sought after Venetian glass pearls. These old Indian copies are not refined as the original Venetian pearls. However they have their own charm in their more 'primitive' design.

|

|

|

|

largest beads in upper chain: 13 * 9 mm

Click on picture for larger image

Brm - Glass 3

UNFORTUNATELY THESE BEADS ARE NOT GENUINE BUT COUNTERFEIT SPECIMEN

|

|

The Pyu City-States and the Indian Buddhist Influence

The most remarkable and aesthetically pleasing beads

from Burma predominantly originate from the

Pyu city-state culture. As evidenced throughout this

page, these artifacts represent a vast assortment of

bead types.

A Snapshot of Burma's Pyu City-States

The Pyu city-states, known

for their prosperity and peace, had an impressively long

lifespan. They began around 200 B.C. and gradually

declined around 1050 A.D. Visitors from contemporary

China characterized the Pyu city-states as both affluent

and tranquil. Chinese chronicles observed that young Pyu

monks chose to wear cotton silk rather than genuine

silk, thereby sparing the lives of silk worms.

The Indian Influence on Pyu's Culture

Although the Pyu people descended from a Tibeto-Burmese

tribe originating from the Yunnan province, they quickly

fell under the extensive influence of India.

Indian Ashokan Buddhism, followed by Gupta influences,

permeated every level of Pyu society, facilitated by

far-reaching trade relations. This influence was

particularly apparent in the southern Pyu areas where

the most significant maritime trade with India was

conducted. Here, the process of 'Indianization' was

highlighted by southern kings of Sri Ksetra adopting

Indian titles like Varmans and Varma.

Both the southern and northern Pyu states were

influenced by India. Some northern Pyu Kings (Tagaung)

even asserted their lineage from the Sakya clan of the

Buddha.

Buddhist India: A Super Power

With a population not exceeding a few hundred

thousand people at their peak, the Pyu city-states were

small in size. Such a limited population lacks the

critical mass necessary to create a fully independent

society.

Contrastingly, ancient India was a vast empire, hosting

one of the world's largest populations. With King

Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism, India became the ruler

of the world's most substantial economic power.

Evidence of the deep Ashokan Indianization can be found

at numerous Pyu sites, which have unveiled a wide

variety of Indian scripts. These range from King Asoka’s

edicts written in north Indian Brahmi and Tamil Brahmi,

dated to the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, to the Gupta

script and Kannada script, dated to the 4th to 6th

centuries AD.

The countless stupas and pagodas in Bagan, encapsulating

a purely Indian Buddhist architectural style, likely owe

their construction to Indian engineers and architects.

Ruled by independent kings, the Pyu settlements

established courts heavily influenced by the Indian

monarchy, particularly the southeast region of India.

Kings and Monks

Under the

influence of Ashokan Buddhism, Kings were not considered

inherently divine. Instead, their legitimacy was

sanctioned through a symbolic 'baptism' by Buddhist

institutions. The people of Pyu, and later the Burmans,

adhered to the original state Buddhism of the Ashokan

empire. This created a symbiosis between monasteries and

the state, whereby Kings could not exist without being

divinely ordained by the Theravada institutions.

From the inception of the Pyu culture to the English

conquest of Mandalay in 1885, Buddhist monks played a

crucial role in sanctifying Burmese kings. Monks

performed the necessary rituals to validate the

monarch's divine right to rule. In return, royal

families provided financial support to the Sangha (the

monastic community). This system, which slowly faded in

India with the rise of the Sunghas, continued in Burma

until the English extinguished the royal classes during

the last Anglo-Burmese war in 1885.

Animist Buddhism

By the 4th century, the Pyu had largely embraced

Buddhism. However, akin to contemporary Burma, the

practice of Buddhism often layered over a deep-rooted

animistic core. This blend of beliefs is akin to the

creation of Burmese lacquer art - beneath many layers of

lacquer, the innermost core is made of animal horse

hairs. In essence, the Burmese culture remains

fundamentally animistic. The interpretation of Burmese

Buddhism should be viewed within this animistic context.

This also applies to the bead culture and the associated

magical beliefs attached to beads, which reflect the

spectrum between

Animism and Buddhism.

The Ascendancy of the

Burman Culture

Around 800 AD, the Burman culture began to slowly

replace the Pyu culture, initiating from Bagan. A

recurring theme in history is the tendency of the

victors to adopt the culture of the defeated, and the

Burmans were no exception. A poignant illustration of

this is seen in the actions of the new Burman ruler who

assumed an entirely Indian name, King Anawrahta. In

1044, when he declared his conversion from Ari-Buddhism

to Theravada Buddhism, he commissioned the building of

the Schwezigon Pagoda. Interestingly, this pagoda was

constructed in the distinctive architectural style of

the Pyu.

Schwezigon Pagoda, Bagan, 1044

Buddhists and Hindus:

Co-existing Cultures

The civilizations of the Pyu and later the Burmans were

predominantly Buddhist, however, they had a significant

and respected Hindu minority, mirroring the religious

diversity of India. Regrettably, much evidence of a

prosperous Hindu culture in Burma was systematically

destroyed following the military coup in 1962. For

instance, in Bagan, several hundred ancient Pyu

Shiva-lingas were demolished as part of the

military's efforts to eradicate all Hindu cultural

influence in Burma. Simultaneously, millions of Indians

who had settled in Burma during the British colonial

period were expelled from the country by the new

military dictatorship.

The

Evolution of Bead History

The trajectory of bead production mirrored the

political shifts in power, as the production techniques

and styles were appropriated by the ascendant Burman

rulers. Consequently, distinguishing between an

authentic Pyu bead and a bead crafted by the subsequent

Burman artisans of Bagan can sometimes be challenging. I

had the privilege of interacting with a group of Burmese

individuals whose livelihoods depend on bead hunting.

From my experience, they are the most adept bead experts

I've encountered throughout my time as a bead collector.

They maintain that they can easily differentiate between

a Pyu bead and a later Bagan-Burman bead, attributing

the decline in the quality of bead making to the period

following the Pyu civilization's decline.

Certainly, Pyu beads possess a distinct identity and

artistic allure. However, it's critical to remember that

these beads, along with their designs, served as vessels

of cultural and religious symbolism, largely influenced

by the Buddhist epicenter, India.

In examining the design and symbolic significance of Pyu

and subsequent Burmese beads, it's essential to consider

their well-documented connections to and dependencies on

Indian trade. Furthermore, it's important to remember

that during the Pyu era, India was a predominantly

Buddhist country. Thus, all beads from this period, and

even those created later, should be interpreted in the

context of the syncretic blend of Animistic and Buddhist

traditions in Indian culture.

Presently, Pyu bead culture is often misinterpreted as

an isolated phenomenon, akin to the erroneous perception

of Gandhara art as a cultural artifact exclusive to

Afghanistan. However, Gandharan art wasn't merely a

local artistic expression; it was an integral part of

the flourishing State Buddhism of Greater India.

Below, I've displayed a selection of etched beads that I

procured in Bagan. These beads share an identical design

with the ones I discovered in Northwest India and

Pakistan. As it often happens, beads can be seen as

voyagers — on one hand, they lose their historical

context through travel; on the other hand, they actively

contribute to the creation of history through their

journey.

Beads from Bagan, Burma

Beads from Northwest India

Assessing the

Age of Pumtek Beads

In the West, Pumtek beads are often classified as Pyu

beads. However, during my visits to Burma, I found that

local diggers, collectors, and bead sellers do not

acknowledge this classification. Many were not even

familiar with the term 'Pumtek', referring to these

beads simply as 'Chin beads', indicating their origin

from the Chin province in Northwestern Myanmar. This,

combined with my historical investigations, led me to

formulate the following hypothesis:

At the onset of the Pyu culture, there was no distinct

or remarkable bead culture in Burma. Similar to the

architectural styles of the pagodas, the lives of the

Kings, and so forth, the prevailing cultural elements

were largely modeled after those of their Indian

Buddhist neighbor. Consequently, the earliest beads

discovered in Burma exhibited purely Indian designs,

either produced in India or by Indian-influenced

artisans residing in Burma. It was only later that the

various tribes of Burma began to cultivate their own

styles and techniques of bead making.

This evolution mirrored the progression observed in the

development of stupas and pagodas in Burma. Initially,

structures at Bagan were purely derivative of Indian

architecture. However, as the Burman culture expanded

and exerted influence over neighboring tribes and

regions, Burma started to develop its own distinct style

of stupa and pagoda architecture.

Bagan-Indian cloned stupa style

One of the primary

characteristics of Pumtek beads is that they are made

from petrified or agatized wood, a material not found in

India but abundant in Burma. Therefore, Pumtek or 'Chin'

beads could be seen as representing a later, more

'localized', and independent progression in Burmese bead

making. Interestingly, this development did not occur

within the historical centers of power in Burma, but

rather at the periphery of the country.

At present, I do not possess sufficient evidence to

confirm this hypothesis; it remains a working model.

However, if considered from this perspective, Pumtek or

'Chin' beads may not be as ancient as previously

thought, potentially not exceeding a maximum age of 1000

years.

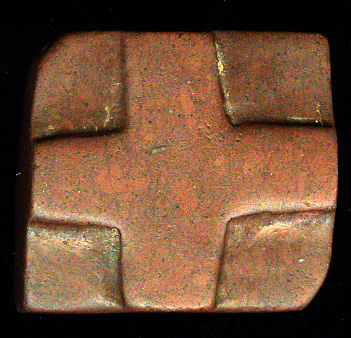

The Significance of the

Buddhist Cruciform

One of the most prevalent symbols observed on Pyu

beads is the cruciform.

While the Pyu civilization

had a particular fondness for this symbol, it did not

originate from their culture but came as a messenger of

Buddhism from India.

Cruciform stupa structure

of Somapura, Greater India

The cruciform held

significant importance in early Buddhism and was

integrated into the architecture of most stupas and

pagodas. To explore this connection, I presented several

well-learned Buddhist monks in Myanmar with cruciform

beads, such as the one displayed below, and asked them

about their initial impressions of this symbol.

Interestingly, even though most of these monks had never

seen these cruciform beads before, their responses

aligned with my expectations.

"This symbol depicts the Four Noble Truths of the

Buddha..."

"This symbol signifies the mission of the Buddha, akin

to what is portrayed in the Ashoka pillar..."

Buddhist Cruciform Jasper Bead

|

|

|

|

26 * 24 * 9 mm

Click on picture for larger image

|

Again, the

profound influence from Indian Buddhism is evident. This

pre-Christian cross was the emblem of the renowned

Buddhist University at Taxila in Northwest 'Greater

India'.

Below you can see a bead from Taxila in Pakistan.

Below, you can see a bead

from Taxila in Pakistan. I firmly believe that the

patterns depicted on etched beads represent a simple

sign language rooted in Buddhist culture. These

straightforward signs, like the uncomplicated mudras of

the Buddha, served to unify various Buddhist societies

scattered along the vast expanse of the trade routes.

These diverse Buddhist cultures had different customs

and languages, but they found common ground in

understanding the humanistic messages of the Buddha.

These messages promoting tolerance and human

understanding were essential for the maintenance of the

trade routes. You can read more about this subject [here].

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|