|

|

ANCIENT

CARNELIAN BEADS

Reflecting on Etymology

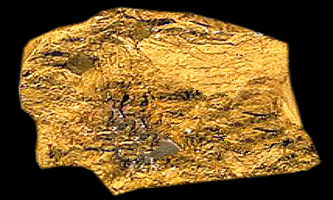

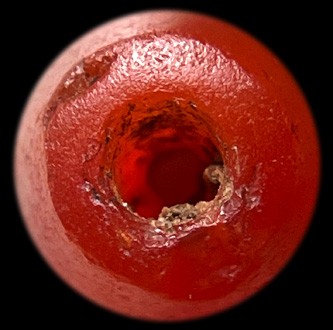

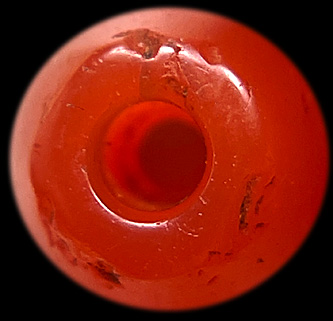

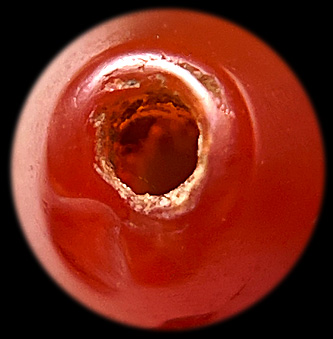

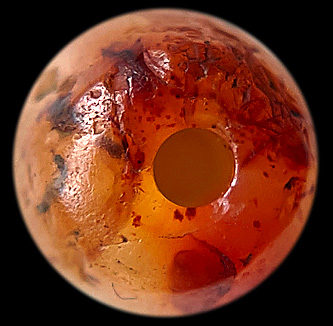

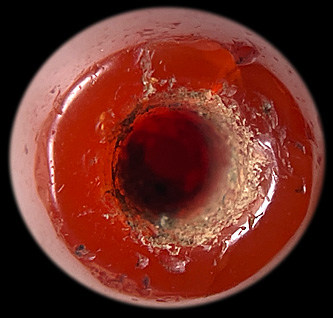

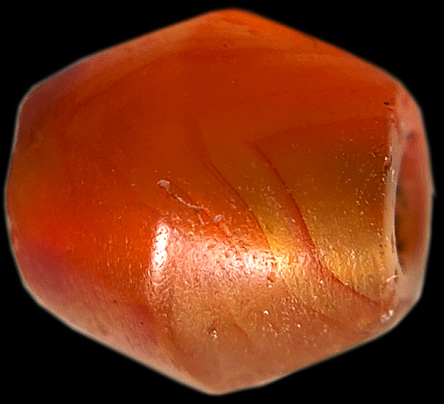

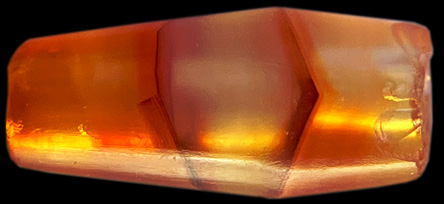

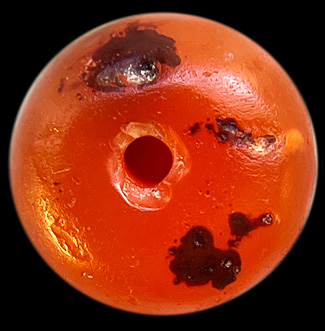

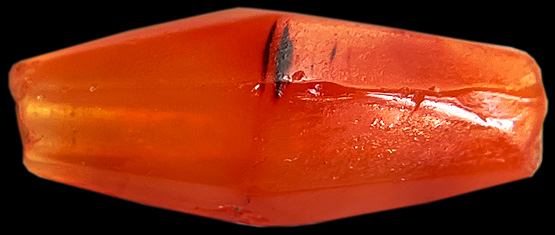

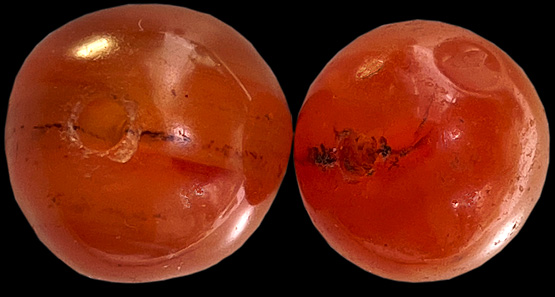

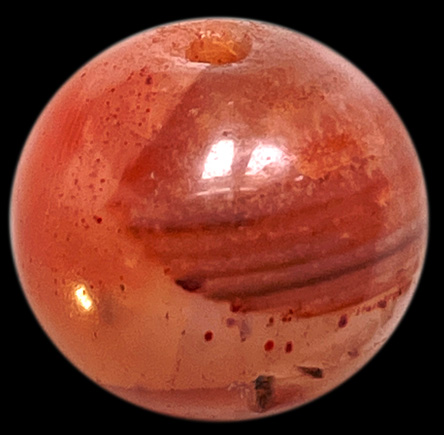

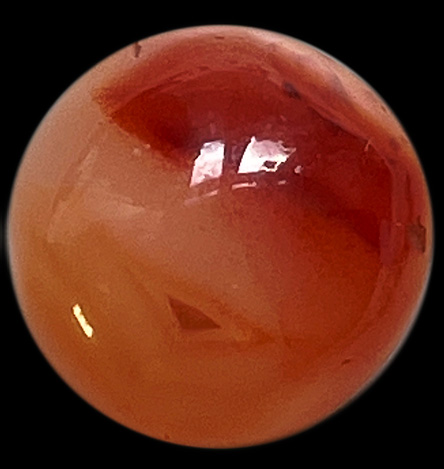

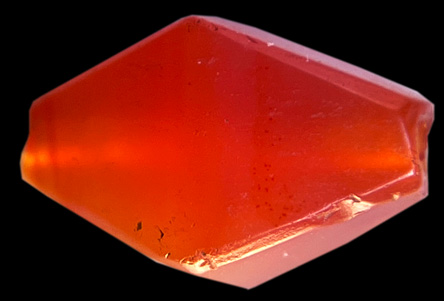

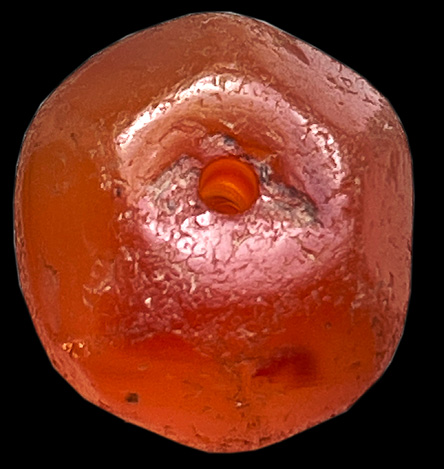

The term 'carnelian'

is widely believed to originate from the Latin word

'Carne,' which translates to 'flesh.' A look at the

semi-precious stone displayed above offers a clear

understanding of why the ancient Romans opted for this

descriptor for this member of the cryptocrystalline

agate family.

Carnelian has been revered as a cherished gemstone since

the Neolithic period.

Evidence of carnelian ornaments and beads can be traced

back to the Bronze Age, with discoveries in the Indus

Valley, Mesopotamia, and Egypt. Subsequently, the

Persians, Greeks, and Romans utilized the stone,

particularly for seal engravings. The stone's enduring

appeal continued into the Medieval period, where the

mystic Hildegard von Bingen extolled its healing

virtues. She proposed that the name 'carnelian' was

derived from cornel cherries, attributing this to the

similarity in color. While Hildegard and others who

support the cherry connection are justified within their

local contexts, the idea of assigning a globally

esteemed stone, treasured since the Neolithic era, a

name derived from cornel cherries seems somewhat amusing

to me.

Egyptian carnelian Tet Amulet

New Kingdom Dynasty - XIX-XX,

1307-1070 B.C.

The Egyptian Book of the Dead signified red as a

representation of blood, and therefore, life and

vitality. The Isis girdle/knot-amulet, known as Tet

(Tyet), was crafted from carnelian and invoked with the

phrase: "Oh, blood of Isis." This amulet was buried with

the deceased and was typically made from a red

semi-precious stone like carnelian or red jasper. In

this context, the Tet amulet was symbolic of the blood,

power, and strength of the goddess Isis. It was believed

to offer protection against all forms of evil and aid

the deceased in their journey through the underworld.

Delving Deeper into the Historical Symbolism

As we trace our steps back through history, symbolic

interpretation becomes paramount. In a world shaped by

magical thinking and analogies, the connections between

the hues of carnelian and blood are compelling and

intuitive. It wouldn't be surprising if the ancient

civilizations of India and Mesopotamia held similar

beliefs, or at the very least, were submerged in similar

layers of Bronze Age symbolic connotations. However, it

was the Romans who coined the term 'carne,' not these

ancient cultures.

The Romans built their civilization extensively on the

foundation of Greek and Greco-Egyptian cultures. Within

this context, it's noteworthy that Isis was the most

widely revered Egyptian deity exported to the

Greco-Roman world. Consequently, it's not inconceivable

that the term 'carne' and the deeper meaning behind it

could have been influenced by the cult of Isis, and by

extension, the ancient river cultures that preceded

them.

Even from a chemical perspective, the association

between 'carne' and carnelian holds water. Iron oxides,

which impart color to both blood and carnelian in the

form of hemoglobin and hematite, draw a clear

connection. If we were to apply

Occam's razor to the world of etymology, the

derivation of carnelian from 'carne' emerges as a

plausible choice.

The European localized cherry could have been an apt

metaphor for Hildegard von Bingen, but even if it were

the true origin of the naming of carnelian, it would

carry many neo-colonial implications. A potentially

incorrect but more historically symbolic, respectful,

and less Eurocentric name might be more appropriate.

This isn't an attempt to introduce 'wokeness' into the

realm of bead study, but a touch of provocative

inspiration from diverse and seemingly unconventional

ideologies can sometimes spark enlightening discourse

Exploring Variations in Appearance and Color

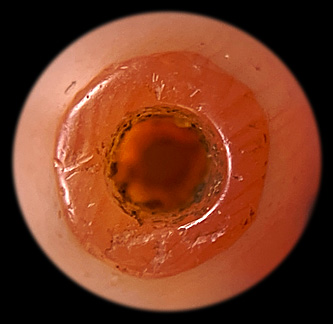

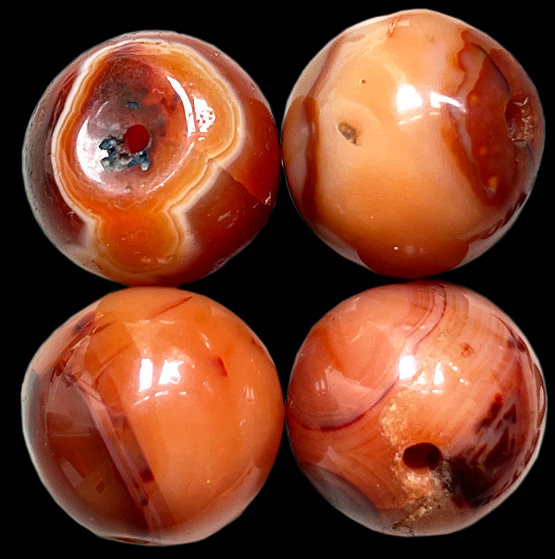

Carnelian, however, isn't just confined to the color

red. It can be found in a myriad of shades, spanning

from yellow to orange to darker shades of red, and even

brown. The luster of the stone can vary as well, ranging

from a waxy or resinous sheen to a creamy or vitreous

gloss. Translucent carnelian is a rarity and is often

highly prized for its unique appeal.

The Significance of Indian Carnelian

Carnelian has been sourced from numerous locations

worldwide, including Australia, Europe, and America.

However, some of the most exquisite carnelian pieces are

believed to have originated from India, a claim

supported by the stunning beads on display here. India

has a long history of shaping carnelian into valued art

objects, a tradition that dates back to the Neolithic

era. This practice did not diminish with the advent of

the Mughals in India.

|

Source:

The Gods

and symbols of ancient Egypt

Thames &

Hudson

Manfred Lurker

Amulets of

ancient Egypt

Andrews

British

Museum Press |

|

|

|

Local folklore in Agra suggests that carnelian was the

favorite gemstone of the beautiful Queen Mumtaz, the

beloved wife of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jehan. When she

passed away, he commissioned the creation of the Taj

Mahal as her mausoleum. In the intricate semi-precious

stone inlay work found within the inner sanctum of the

Taj Mahal, only the finest quality of red carnelian was

used.

Carnelian also plays a central role in the

Pietra

Dura

inlays, found in the white

Makrana

marble used in the construction of the Taj Mahal and the

Red Fort. An example of this artistry can be observed in

the Butterfly Pavilion within the Red Fort in New

Delhi:,

where the vibrant carnelian creates an impactful visual

against the stark white marble.

|

|

|

|

Illustration 1

|

Understanding Carnelian's Mineralogy

The rich and varied colors that carnelian presents

are a result of the incorporation of various iron oxides

and/or hydroxides within its structure. These iron

compounds, particularly those belonging to the hydroxide

group, exist in a multitude of chemical variations. The

relationship between oxygen and hydrogen in these

compounds lends itself to the broad spectrum of color

variations found in carnelian.

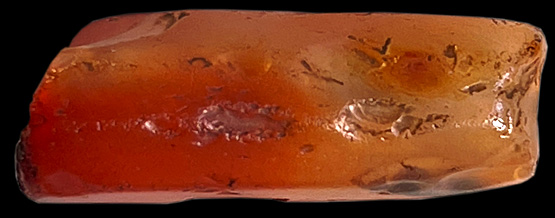

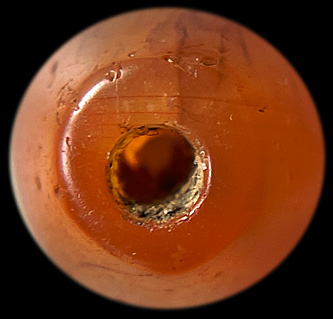

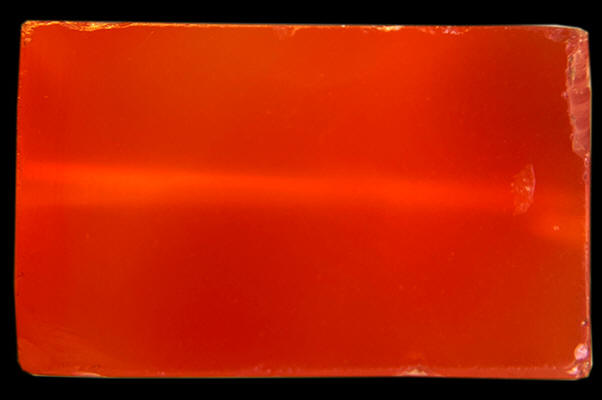

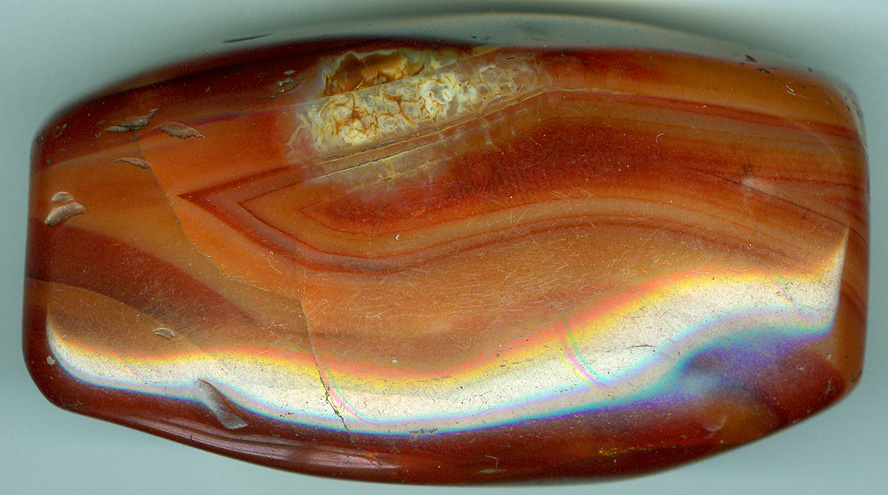

Influence of Hematite

Hematite, an oxide of trivalent iron (Fe2O3), is

particularly influential in giving the stone its vibrant

red color. Observe the color similarity between the

hematite-colored bead shown below and the pietre dure

inlay mentioned above.

|

|

|

|

Hematite mineral

A hematite-carnelian beauty

Read more about this

unique bead here.

|

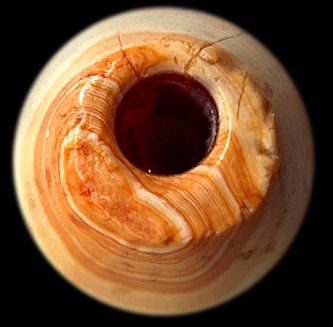

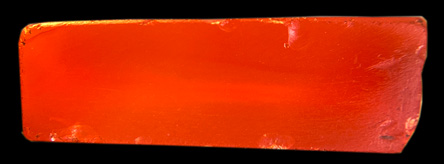

Decoding Limonite's Role

Limonite, a widely prevalent variation of iron

hydroxide in carnelian, takes on the chemical formula

FeO(OH)·nH2O. Limonite and other hydrous iron oxides can

significantly influence the color spectrum of carnelian.

Their presence results in hues that span from yellow and

rusty, to distinctively brown. So, the variety of tones

that carnelian possesses, ranging from yellowish to deep

reddish-brown, can often be attributed to the presence

of limonite.

|

|

|

|

Limonite

mineral

A limonite-carnelian bead

|

|

Carnelian, in its pure and natural form, can be

discovered showcasing a wide array of colors, including

yellow, orange, red, and brown. However, in contemporary

times, discovering natural deep red or orange carnelian

has become somewhat of a rarity. This scarcity is

primarily due to the immense popularity these stones

have enjoyed since the Neolithic era.

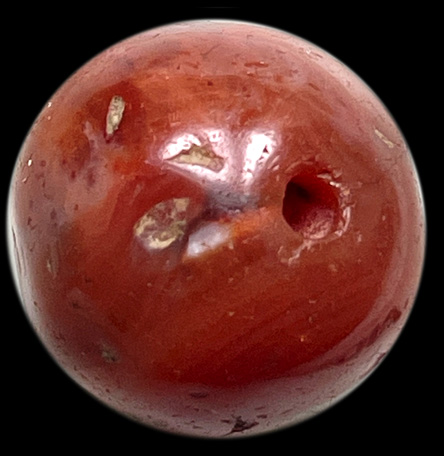

Intense red and orange hues in carnelian are typically

associated with hot climate zones. It is in these

regions that nature's own heat treatment, occurring over

millennia, has gradually transformed the original

hydroxy-based colors into a rusty-looking hematite

carnelian. This is particularly true for Indian

carnelian. Over countless centuries, exposure to the

scorching sun slowly facilitated the conversion of iron

hydroxide into iron oxide, leading to the highly

sought-after red coloration. Thus, it could be said that

the Indian carnelian simply 'rusted' over time.

Intriguingly, carnelian seems to uniquely possess this

quality among the varieties of cryptocrystalline quartz,

becoming more vibrant and attractive when subjected to

heat.

However, by the late Bronze Age, the escalating demand

had started depleting the natural reserves of red

carnelian. This led to the development of techniques to

artificially heat suitable stones to achieve the desired

coloration. In fact, the demand for this captivating

blood-colored stone was so high that natural sun-baked

carnelian became difficult to acquire, even in its place

of origin, India. Consequently, the ingenious

inhabitants of the Indus Valley developed the technique

of transforming chalcedony into carnelian through heat

treatment.

In today's context, when we examine an ancient carnelian

bead, it is virtually impossible to ascertain whether

the stone has undergone heat treatment or not.

A brief enchantment with Carnelian

Observe the photograph below, a tableau I chanced upon

in the Moroccan Sahara, close to Hamid. Here, remnants

of Neolithic flint tools are scattered across the

hardened crust of the desert. Among them is a seemingly

out-of-place stone, a small carnelian piece that appears

to be part of the assemblage of flint scrapers. These

tools were crafted and used by ancient humans at a time

when the Sahara teemed with life, verdant and lush.

Interestingly, this piece of carnelian is strikingly

similar to high-quality carnelian pebbles I've seen from

Lothal,

India.. This leaves us

with a tantalizing question: could there have been an

ancient trade network stretching from Africa to India,

even during these primitive times? Or was this simply a

result of the relentless Saharan heat working its

alchemy on the stones?

Click on the picture for a larger version

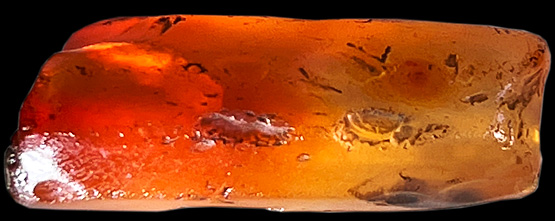

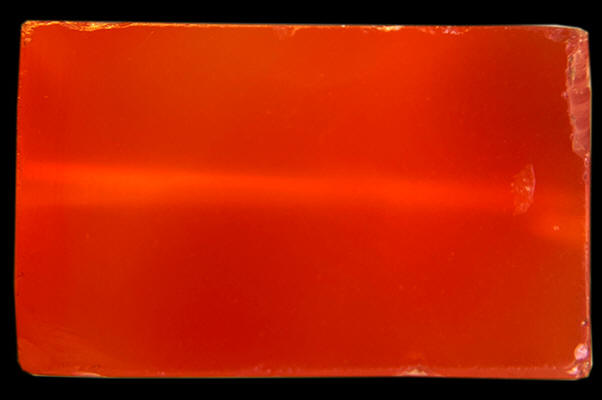

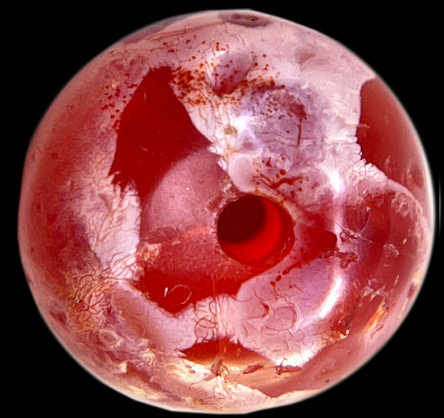

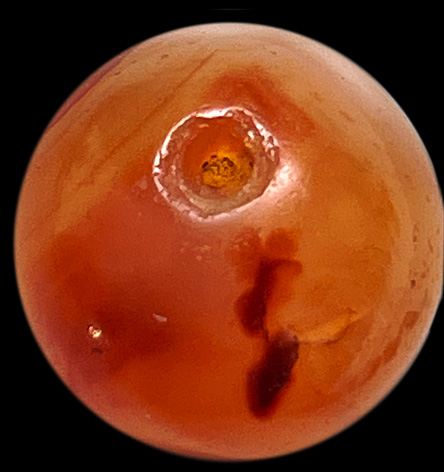

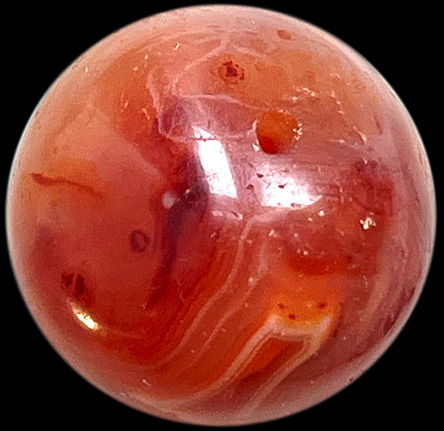

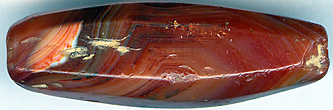

Carnelian of a deep Red-Orange Translucent and

Homogenous color

It's worth noting that there is

considerable variation in the quality of carnelian. Stones that are

translucent and exhibit a uniform color have been most highly prized

since antiquity. The ideal carnelian, be it used for beads or other art

forms, should be free of banding and possess a deep, translucent

red-orange hue. This characteristic is apparent in the ancient bicone

beads from the Indian

Indus Valley,

which are showcased below.

The iron oxides responsible for carnelian's coloring can be uniformly

distributed, as seen in the Indus Valley beads, or they can manifest in

gradients, as shown in the bead pictured above. The iron oxide patterns

can also appear as cloud-like patches, or as reddish specks that are

referred to as 'blood spots' by Tibetans.

Chung DZI with blood spots

Bead Production in

Cambay

Beads are frequent globetrotters, their journey often

seeming ceaseless. But every bead has an origin, a place

where it was created. A large proportion of ancient

carnelian beads discovered worldwide originate from

India. Bead making was widespread throughout the

continent, with locations of production heavily

dependent on the availability of suitable materials.

While agate and jasper can be found in many parts of

South Asia, the scope, diversity, and abundance of

resources in Gujarat is unparalleled. This could explain

why Gujarat, particularly an area known as

Cambay,

maintains a vibrant bead-making tradition. This locale

is where the skills of ancient bead masters have endured

through the centuries to the present day.

More accurately, it's the nearby region of Lothal, a

Harappan outpost, that has served as a stone-working

center since the Indus Valley people began crafting

beads from the region's abundant deposits of carnelian,

onyx, and agate. Lothal dates back around 4000 years,

but the Indus people started bead making and exporting

over 5500 years ago!

The Splendid Cambay Carnelian

The carnelian from Gujarat, specifically around Cambay, is renowned for

its superb red-orange color, as can be observed even in the small

carnelian pebbles from Lothal depicted above. This is primarily

attributed to the region's high iron content.

Since the Indus period, individuals equipped with rudimentary tools have

been burrowing into the iron-rich Miocene agate formations in the

Babaguru formation.

The striking dark red colors are enhanced by drying the stones in the

sun, followed by

repeated heating. The techniques and tools utilized by Indian

artists have changed little since the time of the Indus Valley culture.

Their beads are entirely handcrafted, which results in less uniformity

in size and shape but infuses each piece with a warmth and beauty

distinctive to handcrafted items. Due to their enduring allure, Cambay

remains one of the world's largest stone manufacturing locations. The

region's primary market has traditionally been Africa.

However, according to my friend and esteemed bead expert,

Sanatan Khavadiya, the

deepest red carnelian originated from Aurangabad in Maharashtra! This

serves as a gentle reminder of how much we still have to learn about

beads and the world at large.

The Global Dissemination of Beads Facilitated by Islam

Starting around AD 1300, the bead-making industry in the Cambay area

began to prosper once again. This resurgence was largely due to the

artisans who crafted Muslim amulets, prayer strands, and a vast quantity

of carnelian beads, primarily for the African and Middle Eastern

markets. These goods were transported by Arab traders to East Africa

aboard monsoon-propelled dhows, or brought to Mecca and Cairo before

reaching West Africa via camel caravans. Consequently, Muslims became

significant transporters of beads, primarily due to the religious

imperative of Hajj, which mandates every Muslim to make a pilgrimage to

Mecca at least once in their lifetime, regardless of their global

location. Beads, being easy to carry and exchange for provisions, were

an ideal commodity for these long, arduous journeys.

Islam, an international religion, served as a significant cultural

phenomenon, with Arabic being the lingua franca. At its zenith, Islam

brought together people from diverse races and cultures, creating an

enormous global melting pot. Once a person converted to Islam, their

skin color and native language became irrelevant. Wherever Islam was

present, beads followed, and they became as intertwined as the people

who wore them.

Prior to the rise of Islam, Buddhism served a similar role, facilitating

the spread of beads in contrast to the more feudal and stationary Hindu

caste culture.

The Holy Bead Man, Baba Ghor

Around 1500, the bead industry in Cambay witnessed further expansion,

reaching unprecedented levels of production. This growth was driven by

Muslim settlers, particularly under the leadership of an Ethiopian saint

known as Baba Ghor, or the "Holy Bead Man." His arrival initiated a

period of mass bead production on a scale that was previously unknown.

Cambay vs.

Idar-Oberstein

The Indian bead industry enjoyed a virtual monopoly

on carnelian bead production for many centuries.

However, this position was challenged in the 19th

century when the city of

Idar-Oberstein in Germany began to carve carnelian

beads and ornaments. Idar-Oberstein was renowned for its

gemstone carving and polishing industries, which took

advantage of the high-quality agates found in the

region.

The skilled craftsmen of Idar-Oberstein were able to

create carnelian beads of exceptional quality and

intricate design, exceeding what was produced in Cambay.

Their superior techniques and the use of water-powered

machines for cutting and polishing gave them a

competitive edge, allowing them to produce a higher

volume of beads more quickly and efficiently.

This competition from Germany was further compounded

when Bohemia (now a part of the Czech Republic), known

for its glass-making industry, began mass-producing

molded glass beads that imitated carnelian. These

imitation beads were cheaper to produce and buy, and

they soon flooded the African market, which had been a

major destination for Cambay's beads.

The Indian bead industry struggled to compete with these

new entrants. The superior quality of Idar-Oberstein's

beads and the cheaper price of the Bohemian glass

imitations significantly impacted the Cambay bead trade,

leading to a significant decline in the region's

bead-making industry.

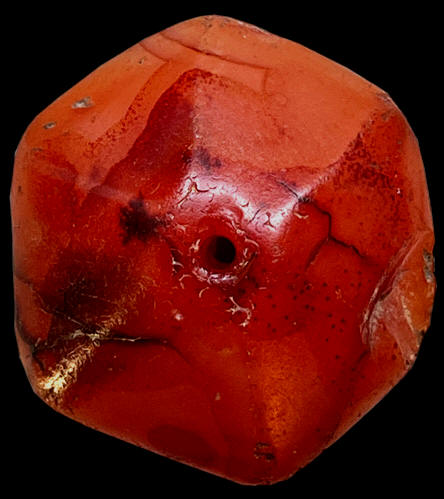

ANCIENT INDUS

BEADS FROM INDIA VIA

MESOPOTAMIA

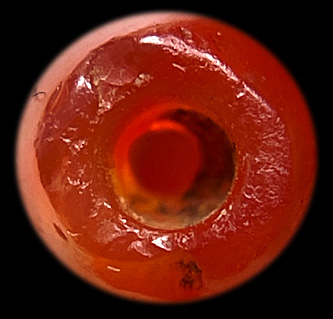

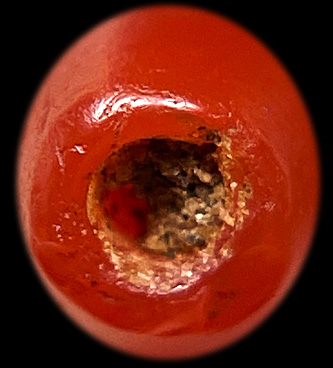

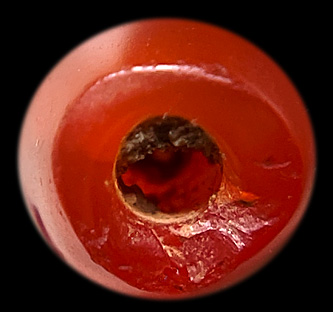

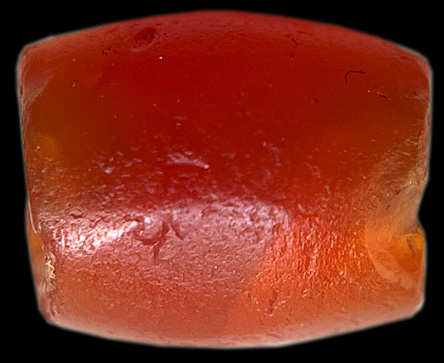

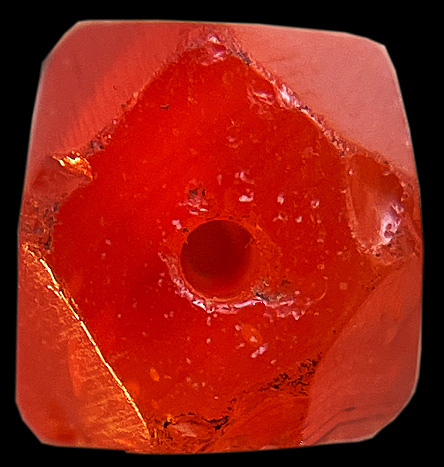

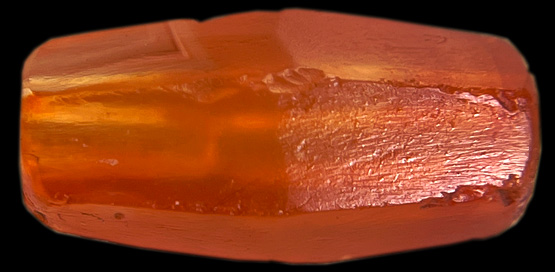

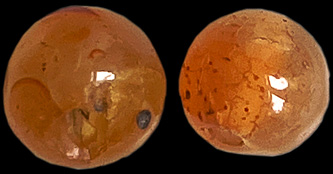

The ancient heptagon-shaped carnelian bead shown below

exudes a sense of timeless beauty. Its surface, etched

by the passage of time, bears the resemblance of a face

adorned with a myriad of wrinkles, each one a testament

to its ancient origins. Under the surface, the bead

reveals a deep, rich red hue characteristic of

high-quality carnelian.

Over the centuries, a thick layer of calcification

has formed on its surface, further attesting to its

great age and enduring allure. This layer is hard and

resilient, protecting the precious stone beneath while

also enhancing its ancient charm. Such relics offer us a

tangible connection to the past, providing invaluable

insights into the history and culture of the ancient

civilizations that crafted and used them.

Although originally from India, these ancient carnelian

beads traveled extensively through trade routes, notably

reaching Mesopotamia. The circulation of these beads

evidences the extensive trade networks and cultural

interactions between ancient civilizations.

|

|

|

|

CARN

1 - 15,5 * 10 mm

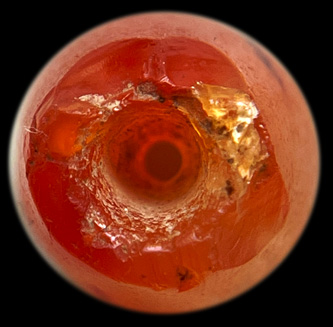

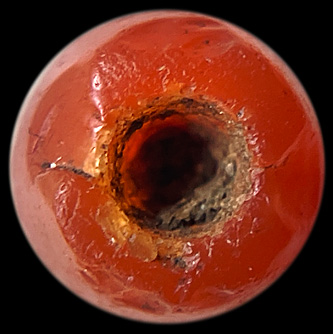

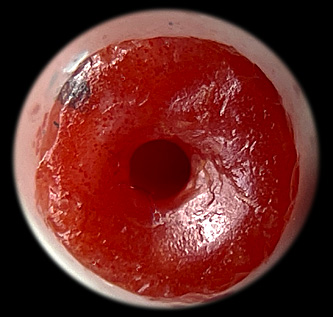

Here I made a cardinal sin by removing most of the

calcified layers.

By doing so, the inner translucent color-quality of the

carnelian stone is able

to come out. I consider this one of the most beautiful

carnelian stones in

my collection. After this radical cleaning, the bead

shines

with a bright red color even in an ordinary light

setting.

|

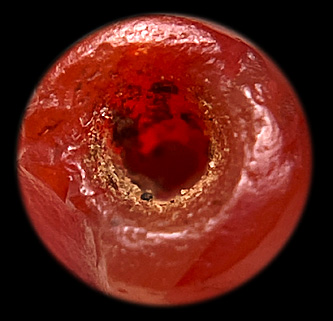

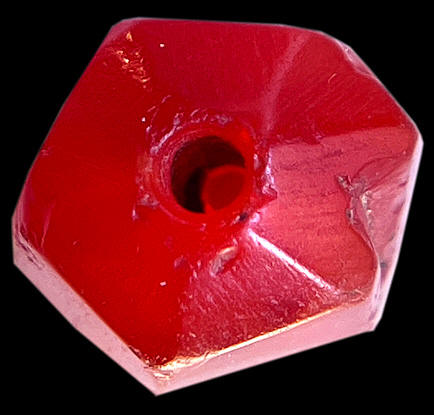

The hexagonal beads

showcased here bear the visible markings of substantial

wear and tear, contributing significantly to their

surface alterations. Considering their chemical layers

and wear-induced polish, they stand as some of the most

transformed pieces within my collection. One might

question whether the carnelian from which these beads

were crafted is softer than the average carnelian,

leading to the pronounced changes. However, this seems

unlikely. Instead, their current condition can be best

attributed to substantial age, combined with extensive

use and exposure to natural elements.

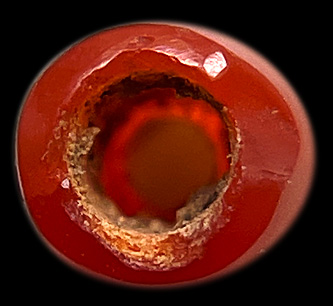

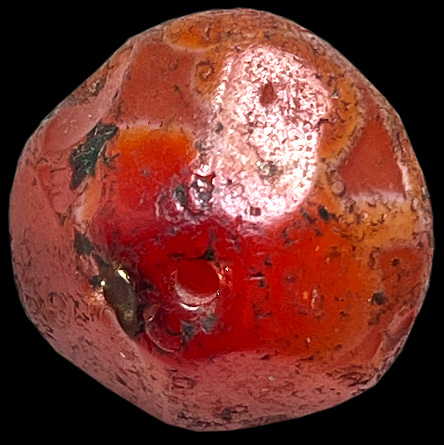

The standout deep-red carnelian bead displayed above

holds a unique history. Unearthed by a Danish

archaeology professor during excavation works, it was

found amidst a collection of more primitively shaped

stone beads in a

Neolithic grave located in the Moroccan Sahara.

Given the timeframe of the surrounding settlements —

known to have existed during the Saharan wet period,

dating from 8000 BC up to 3000 BC — this bead is

estimated to be around 5000 years old. As the climate

shifted, the Sahara began its transformation into a

desert around 3000 BC, prompting the resident

hunter-gatherer communities to gradually abandon the

region.

GO2 more Mesopotamian style carnelian beads

|

|

|

|

|

-----

INDUS VALLEY BICONE CARNLIAN BEADS

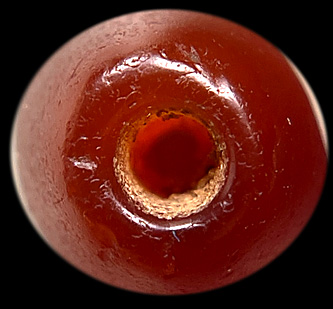

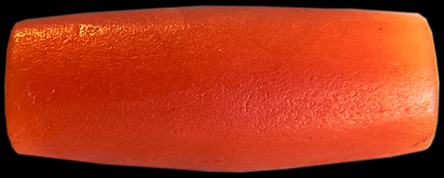

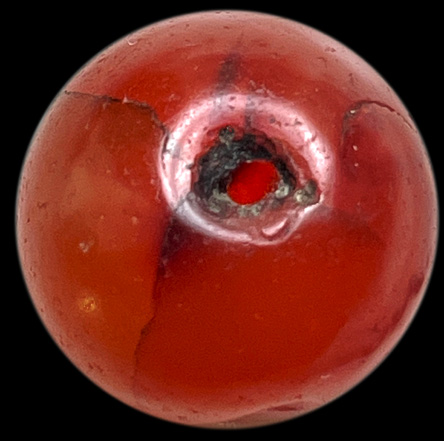

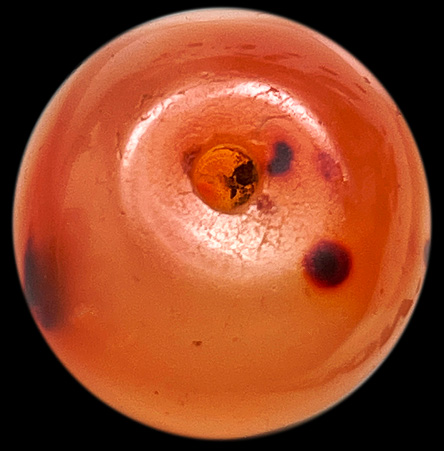

Displayed below, you will find carnelian beads with a

more orange color. The colors and translucency of these

beads are perfectly homogeneous.

|

|

|

|

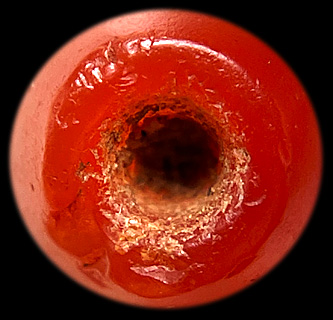

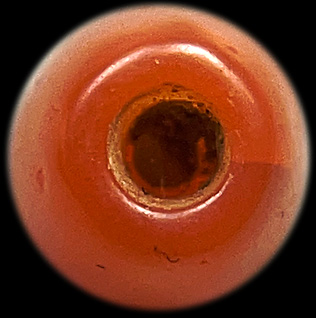

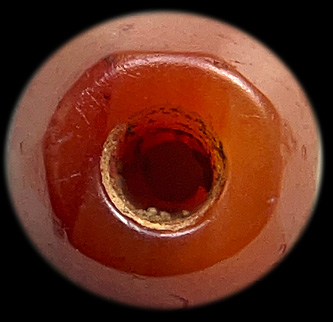

NB!

It is here important

to mention that most beads only will reveal

their full

potential when magnified through a macro lens and

illumined with the right

kind of light.

An ancient bead will never show its full luster, colors and

patterns without a magnifying lens and the right light settings.

This is especially true for small beads and beads that

display various degrees of translucency.

Translucent beads have by nature a 'hidden' world

inside the stone material of the bead itself, that only

can be fully exposed through extra light sources.

The inner translucency of a bead will only reveal a

minimum of its beauty in an ordinary

light set and setting.

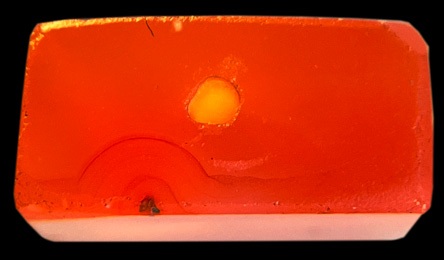

Same bead as above

I have in the exhibition below tried to make a compromise

between the inner and outer life of the beads.

In this way of capturing the beads, imperfections

will be largely exaggerated, as when compared to how the

bead will look in your hand.

I know this will scare away the eastern collector going

for impossible perfection. However, a western conditioned

mind seems to have a liking for 'broken

beauty'.

As a western collector of ancient beads, I share that liking.

Also, bear in mind that the beads appear relatively bigger on

this display.

You can always ask for a more 'realistic' photo taken from my

iPhone.

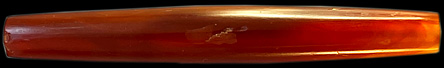

24,5 * 8,5 mm

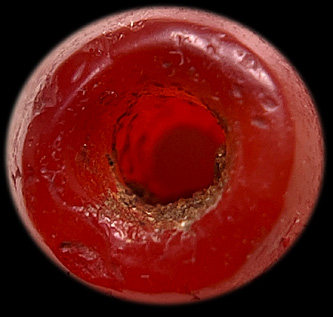

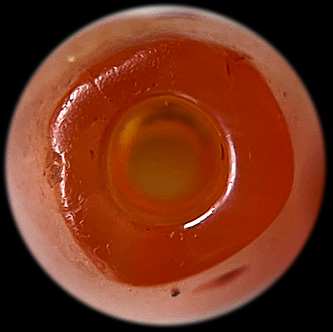

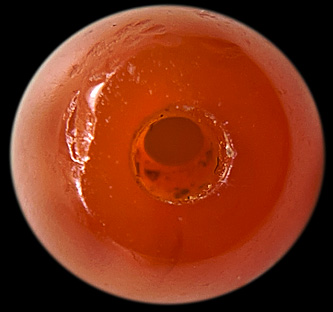

Displayed above you can observe the radical difference

the light setting is for photographing translucent

carnelian beads. In the right light the high quality carnelian

beads will reveal a deep red color, not visible in ordinary

daylight. Hence most of the beads bead displayed below

are much more orange and/or red-colored than what meets

the daylight eye.

|

Displayed below, you will find carnelian beads with a

more orange color. The colors and translucency of these

beads are perfectly homogeneous.

|

|

|

|

The design of this bead is not particular exiting.

It is the carnelian material itself that takes the price!

|

Below you can see a more yellowish, golden variation of

translucent carnelian.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Displayed below you can see wonderful fiery translucent

multicolored colored red-yellow-orange carnelian beads.

Such color-variations are a result of various blends of

iron oxides and hydroxides. |

|

|

|

|

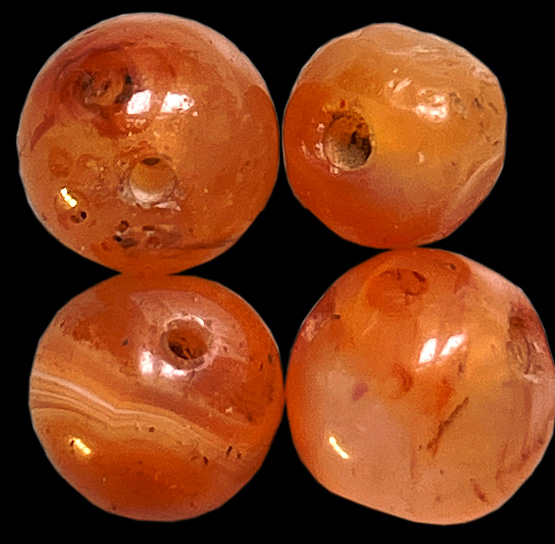

Small top quality carnelian beads

The small ancient beads displayed below are

naturally marked by time. However, the quality of the

carnelian with its deep uniform transparent orange-red

color is still second to none. Such ideal carnelian is

mostly found in smaller pieces.

|

|

|

|

|

However, in rare cases, we can find larger beads with a

unique homogeneous deep red luster, as seen in the, by

now famous specimen below

|

|

|

|

|

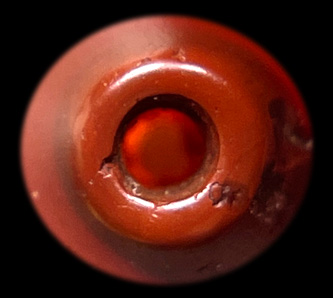

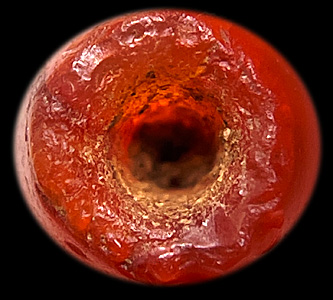

SMALL BICONICAL INDUS VALLEY CARNELIAN BEADS

The beads displayed below are typical for the Harappan

Indus Civilization, with their special bicone-shaped design and large,

hourglass shaped

holes.

The Indians call this shape the dholak design

named after their ancient double drum.

You can see

this type of beads displayed

in the National Museum in New Delhi or in the

British Museum. Below we can observe the same beads found in both an

Egyptian and Mesopotamian grave.

One can clearly see the Harappan

origin of these beads. |

|

|

|

Egyptian neclace -

Walters Art Museum

Mesopotamian neclace from Ur -

British Museeum

|

The biconical carnelian Indus beads displayed here have

been photographed in such a way that their inherent red

color is revealed. Seen from a distance in normal

day-light, they would have a color closer to the ones

from the Egyptian necklace above.

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 1

- 8,8 * 7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 2

- 8 * 8 mm |

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 3 - 9,8 * 8,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 4

- 11 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

5 - 12,1 * 8,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 6

- 10 * 7 ,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 7 - 14,2 * 7,5-9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

8 - 8 * 7,4 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 9

- 10,1 * 7,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 10

- 8,5 * 7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

11 - 8,6 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 12 - 9,9 * 7,1

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

13 - 9,6 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 14

- 9 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 15 - 10 * 7,1-5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 16 - 10,7 * 6,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 17 - 11 * 5,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 18 - 8,9 * 6,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

19 - 8,7 * 7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

20 - 10 * 8,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 21

- 10,2 * 8,5 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 22 - 9,5 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 23

- 10 * 7,1-5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 24 - 18 * 12 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

25 - 9,9 * 7,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 27

- 16 * 11 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

28 - 11 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 29 - 11,2 * 7,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

30 - 13,9 * 8,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 31 - 12,1 * 10 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 32 - 12,8 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

33 - 10 * 9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

34 - 11 * 7,7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 35 - 10 * 9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

36 - 9,5 * 7,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 37 - 8,5 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 38

- 9,9 * 8,8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

39 - 8,2 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 40 - 9,2 * 7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 41

- 9,6 * 8,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

42 - 8,5 * 8,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 43 - 9,5 * 8,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 44 - 9,2 * 9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 45 - 10 * 6,8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 46 - 10 * 7,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 47 - 9,1 * 8,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 48 - 8,5 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 49

- 9,2 * 7,1-3 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 50 - 11,5 * mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS

51 - 9 * 6,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 52 - 8,1 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS 53

- 8 * 7 mm

|

Please note the change in proportionality in the section

to come. The beads above are not as big as they could

seem in comparison to the following display.

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS - LOT 54 - bead to the right: 10,7 * 5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS - LOT -55 - bead in the middle: 9,5 * 5,2 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS - LOT - 56 - lowest bead: 11,2 * 4 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS - LOT - 57 - lowest bead: 12,7 * 3 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS - LOT - 58 - Cornerless cubes - lowest left: 11,5 * 10 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS - LOT -59 - lowest left 7 * 6 * 4 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT - 2 - lowest bead: 16,5 * 6,5 * 4 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 3 - 18 * 11,8 * 7,2 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 4 - 18,5 * 11 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 5 - 13,5 * 6 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 6 - 16,2 * 8 * 6,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 7 - 15,5 * 7 * 6,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 8 - 16 * 7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 9 - 26,3 * 11 mn

|

|

|

|

CARN-INDUS-MESOPOTAMIA

1

- 10 * 9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 10 - 11,5 * 9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 11 - 15 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS LOT 60 - largest: 13 * 5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN LOT 12 - Yellow down left: 6 * 4,2 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS LOT61 - 8,5 * 4,8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS LOT 62 - standing left: 9,9 * 4 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS LOT 63 - down right: 7 * 4 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN LOT 13 - upper: 7 * 4,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN LOT 14 - average 5 mm

Relatively larger than shown in proportion

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS LOT 64 - down right: 10,5 * 7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 65 - 9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 66 - 15,5 * 8,2 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 67 - 15 * 5,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 68 - 7,5 * 5,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 69 - 13,5 * 9,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 70 - 11 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 71- 12 * 11 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 72 - 10-11 * 8,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 73 - 6,8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 74 - 9 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 15 - 11,5/12 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 16 - 8 * 4,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 75 - 15,2 * 11/9,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 76 - 13,5 * 8 * 7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 77 - 11,2 * 10 * 9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 17 - 14,1 * 6,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 78 - 15,2 * 6,2 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 79 - 32,2 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 80 - 49 * 6 mm

Relatively longer than shown in proportion

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 81 - 42,8 * 5,8 mm

Relatively longer than shown in proportion

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS LOT 82 - Lowest: 29 * 5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 83 - 13,3 * 7 * 3,2 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 18 - 51 * 13 mm

Relatively larger than shown in proportion

|

The octagon shaped bead

above and the family o similar designed beads here could

easily be confused with antique beads from

Idar-Oberstein. However these designs have been around

since the Indus-period.

However, as displayed above the drill technique for

making the hole is ancient, in this case more than 1500

years.

|

|

|

|

CARN 19 - 41 * 10,2 mm

Relatively larger than shown in proportion

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 84 - 21,6 * 8,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 85 - 24 * 7,2 mm

|

Displayed above: A

hexagon Indus bead

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 86 - 22,1 * 6,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 87 - 20 * 6 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 88- 23,5 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 89 - 16 * 7,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 90 - 17,5 * 6,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 91 - 14,5 * 6,2 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 92 - 12,1 * 6,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 93 - 10,1 * 6,6 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 94 - 16.9 * 5,6 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 95 - 17,1 * 6,8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 96 - 18,5 * 6,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 97 - 15,1 * 6 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 98 - 14,5 * 6 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 99 - 13 * 6,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 100 - 11,8 * 6,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 101- 14 * 5,9 mm

|

|

|

|

--

CARN INDUS 102 - 13,5 * 5,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 103 - 18,5 * 6,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 104- 11,5 * 5,8 mm

|

|

Please note the change in proportionality in the section

to come.

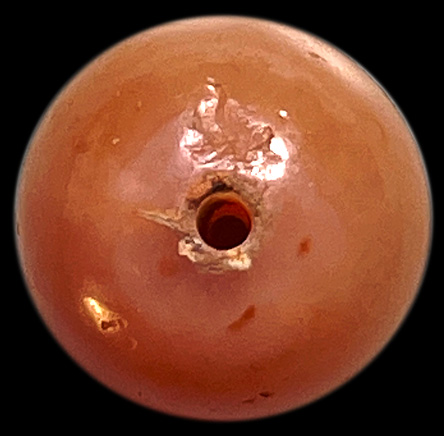

Ball shaped carnelian beads |

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 20 - Upper left: 17 * 13,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 21 - Left: 15 * 14,8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 22 - Upper Left: 17 * 14,8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 23 - Left: 15 * 13,6 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 24 - Upper left: 10,5 * 9,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 25 - 7-8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 26 - Lower left: 10 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 27 - Lower right: 11-10 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 28 - Left: 12 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 29 - Left: 14-13 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 30 - Lower left: 12,5-11,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 31 - Low left 9,5-8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 32 - 8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 33 -

Lower left: 12-11 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 34 - Lower left: 14 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 35 - Lower left: 14-13 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 36 - 17 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 37 - 19-18 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 38 - 18 - 17,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 39 - 12-11,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 40 - 15 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 41 - 17 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 42 - 12 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 43 - 18 * 16 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 44 - 17 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 45 - 12-11,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 46 - Low: 13 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT 47

|

|

|

|

CARN 48 - 24 * 23 * 7,2 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 49 - 27 * 23,5 * 9 mm

|

Two amulets. The above

from India. Below from Sahara.

|

|

|

|

CARN 50 - 28,5 * 12 * 12 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 51 - 33 * 9,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 52 - 20 * 6 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 105 - 14 * 9 * 5,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 53 - 22,5 * 14,2 * 7,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT INDUS 106 - Disk shaped - lowest bead: 12,5 * 4,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 107 - 11 * 10 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN - LOT INDUS 108 - lowest bead: 15 * 11,3¨* 5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 108 - 16 * 9,5 * 5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 109 - 15 * 9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 110- 14 * 11 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN INDUS 111 - 15 * 12,5 * 5,5 mm

|

|

|

|

|

|

CAMBEY CARNELIAN BEADS

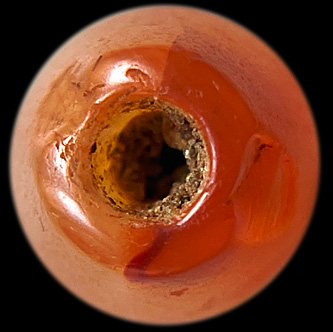

The huge non-transparent bead below was sourced in

Punjab, India. As one can observe on the sharp edges of the hole, this

super-large and heavy carnelian bead has never been used,

or at least not much. It looks new. However, the discoloring made by calcium in the earth reveals that this bead actually is ancient.

I have found exactly similar beads in Africa. In

the section with

African

Fulani Beads, you can observe these beads.

|

|

|

|

CARN 54 - 60 * 31 * 28 mm

This bead does

have banding. So one could also call it a red agate bead.

However this is a distinction without

a much difference,

as both are red-orange cryptocrystaline

quartz.

|

|

This bead is an example of the huge bead trade from

India to Africa going on since ancient times.

Fulani bead sourced from

Africa

|

|

|

|

|

|

CARN 55 -

|

|

|

|

|

CARN 56 -

|

|

|

|

|

CARN 57 -

18 * 13 mm - SOLD

Hexagon

Moroccan Sahara

|

|

After this find, I went to Morocco and found a few

similar beads in Marrakech. I was extremely lucky to

purchase some on the internet too.

Indus beads made for export

According to the bead expert Malik Hakila, the facetted

carnelian beads above and below display the typical

carnelian orange-red shine that in ancient times only

carnelian from the area around Cambey in India had.

However, we don't find facetted carnelians beads in the

Indus Civilization. As we can observe through bead

history, every geographical area in every historical time

had its own favorite beads with certain patterns, shape,

material, and color. The Indus people did not seem to

like facetted beads, but the Mesopotamians did.

Accordingly, my best guess is that

this wonderful polygon highest quality carnelian disk

bead and the ones you see below were made as long back

as by Indus people for the export to the Mesopotamian

Proto Elamite

elite in the Early Bronze Age. According to science, the trade between the

advanced urban civilizations of Mesopotamia and the

Indus began around 2600 BC. For this facetted Indus

carnelian bead to end up in a Neolithic grave in

Moroccan Sahara, we must at least extend this relation

back to 3000 BC and maybe even further! Some historians

relate the earliest Proto

Elamite script with the Indian Dravidian language,

which points at the existence of an Elamo-Dravidian culture

stretching all the way from the Gulf to India. Seen

in the light of the Elamo-Dravidian connection, bead-making and

exporting relations between the two areas might very

well open up for the possibility of an Indus bead ending

up in a Saharan Neolithic grave.

The Proto Elamites had trading

relations with Neolithic cultures as far as northwest

Africa. For the Neolithic people in west Sahara the Proto Elamites were

the closest 'higher' trading civilization at the time of

the decline of water in the area.

So this super ancient bead most probably ended up here due to the exchange

of goods with contemporary but more far more advanced cultures further

east.

Remnants from several Neolithic

settlements can be found in the Moroccan Sahara. For sure, these Neolithic

cultures did not have the technology to

fabricate polished polygonal-shaped beads.

As you can see here, Neolithic beads

from

West Sahara have a far more 'primitive' design equivalent to their

technological level in general.

|

|

|

|

Neolithic Crystal beads from West Sahara - 12 * 5 mm

|

|

From India to Nigeria

Beads are indeed great travelers, and their journey is

often proportional with their age. The beautiful and

large heptagon bead displayed below was a part of an

ornament from the Kings of Benin, Nigeria, 1000 to 1300

A.D. It might have been ancient way before it reached

the African mainland. Note the extremely high quality in

the carnelian material itself. It is rare to find such a large

bead with this ideal deep orange-red translucent and

perfect uniform Cambey color. It does not look so old as

the other beads, and this bead shape was produced for

thousands of years after the Indus period. However the

carnelian itself points to the same period as its more

torn and worn brothers.

|

|

|

|

CARN

58 - 22,5 * 12, 5 mm

Heptagon carnelian bead

|

In the Danish National Museum in Copenhagen, there is said to be an exactly

similar bead to the one displayed above, woven into the dress of a

chieftain from Papa New Guinea! This particular bead has never been in

the possession of Europeans. Most probably it went eastwards from

India via Chinese sea trading routes to Papua New Guinea.

Displayed below is a ancient pentagon-shaped carnelian bead

sourced from the Harappan Indus

culture in Pakistan. As mentioned, it is rare to find this type

of bead in the Indus area.

|

|

|

|

CARN

59 -

17,5 * 13 mm

Pentagon

bead

|

THE TALISMANIC

POWER OF ANCIENT BEADS

I love that the bead displayed above has become softly rounded through

contact with countless generations of human skin. Again we find the

highest quality of carnelian. The discoloring of the bead has been made

by earth and time.

The ancient signature

Why love beads that show extreme wear and tear?

Because they have wrinkles like a face of an old wise man.

Because they are imperfect. Perfection has no spiritual life.

Young people are seldom spiritual. Spirit grows with age in both beads

and humans.

These worn-out beads are perfectly imperfect.

Time has put its mark on them like the softly rounded stones on the beach.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CARN 60 - 18,2 * 11 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 61 - 23-22 * 11,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 62 - 18 * 12,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 63 - 25-24 * 12 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 64 - 15,9 * 9,3 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 65 - 13,5-13 * 7,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 66 - 20-19,5 * 12,1 mm

|

I do not have many beads in my collection that has been so much polished

by wearing as the beads displayed here. These beads must be super ancient. Carnelian has a hardness on

the Mohr scale between 6,5 to 7. Imagine how much time in contact

with human skin it need to make beads like the ones you see here!

|

|

|

|

CARN 67 - 18 * 10,2 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 68 - 19,5-18,5 * 13 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 69 - 18 * 15 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 70 - 15 * 12 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 70 - 16 * 13 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 72 - 17 * 11 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 73 - 16 * 13 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 74 - 21-18,5 * 10 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 75 - 16,5 * 13 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 76 - 18 * 10,1 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 77 - 19-17 * 14 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 78 - 12,5 * 12 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 79 - 15 * 10 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 80 - 14,5 * 9,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 81 - 17-16 * 11,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 82 - 16-15 * 8,5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 83 - 12,5 * 10 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 84 - 17-16 * 10,9 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN LOT 85 - left Middle: 12,8 * 8 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 86 - 16 * 12 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN

87 -

20-19 * 11 mm -

Hexagon

Moroccan Sahara

This magick bead has been

polished almost round by time

|

Most

of these beads were sourced from Moroccan Sahara. It shows, what cannot surprise: that the earliest

higher civilizations had trading contact with the hunter-gatherer civilizations which surrounded them. As you can observe on the page

Neolithic beads, most

of the beads displayed here are more crudely made. Only more 'advanced'

societies could make beads like the fine polished and facetted beads

displayed above. Many of them exhibit the highest quality of carnelian.

However, we must also take into the equation that many of these bead shapes were so popular that they were copied and produced in Africa

almost up to up to our time. Patina, wear and tear and the size and

design of holes are therefore most important in the time-lining of them.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From ancient production to Baba Ghors mass-production

Beads like those displayed above were produced for

export by the Indus people from more than 5000 years ago.

You can compare the Indus beads OIV 9 and 10 above with

the beads below to see the similarity in design.

Several of the beads displayed below are most

likely to be 'only' around 500 years old. They are from the

heydays of Baba

Ghor, whom I mentioned in the beginning. The Baba

Ghor beads are, what is easy to observe, made

out of carnelian stones of a far lesser quality than the

much older

Indus beads

above. Baba Ghors export beads are not rare and not as old as the above

high-quality Indus carnelian beads. The holes are smaller. The craftmanship

is primitive but powerful like an African tribal mask.

These beads are still available for collectors, but for how

long?

Is the baba Ghor story a myth?

However, when I look at these beads, they do not seem to

be 'only' 500 years old. They look ancient to me. I

recently talked to an Indian bead expert, who told me

that according to his view, the Baba Ghor story was a

myth. He told me that there since ancient times had been

a huge amount of ancient beads scattered around n the

area. As an example he mentioned an area in Gujarat

called Ghansor, or Naga Baba Ghansor. In this area, like

many other similar people had for generations collected

beads from Indus sites and sold to especially the Moslem

faqirs. Beads like the ones below were then not produced

500 years back but collected from sites since the last

500 years. I tend to believe this explanation more than

the official Baba Ghor myth.

|

|

|

|

|

CARN 88 - 24 * 23 * 8 mm

|

CARN 89 - 24 * 20 * 8 mm |

Click on pictures for larger image

|

|

|

|

CARN 90 - 22 * 20 * 7 mm - SOLD

|

CARN 91 - 33 * 29 * 8 mm |

|

|

|

CARN 92 - 26 * 23 * 10 mm

|

CARN 93 - 29 * 26 * 7 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 94 - 22 * 21 * 8 mm

|

CARN 95 -

25 * 20 * 8,5 mm |

|

|

|

CARN 96 - 15 * 12 * 5 mm

|

CARN 97 - 18 * 13 * 5 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 98 - 39 * 16 mm

|

CARN 99 - 39 * 13 * 9 mm

|

|

Some of the beads above and below are thousands of

years old. Others are from the

times of Baba Ghor.

in the 15. Century. Again others are trade beads from

Idar Oberstein in the 18. Century:

How to tell the difference? Often

wear and tear is the only indicator of age because the

designs of these beads are ancient. They can be

traced back to Indus Culture. A comparison between the

bead designs below with

the bead shown in this Harappan link

will further substantiate this claim. It is unlikely that Baba Ghor and his followers

invented any new bead designs. Most probably, they did as

Muslim conquerors were best at all the new territories

they came to: sampling information and skills from the

already existing cultures. The production in Idar

Obersten again copied the Ghor beads to ensure a

steady demand from Africa. In this way, the Germans made

copies of Indus valley beads.

|

|

|

|

CARN 100 - 23 * 12 mm

|

CARN 101 - 22 * 12 mm |

|

|

|

|

CARN 102 - 22 * 10 mm

|

|

|

|

CARN 103 - 25 * 13 mm

|

CARN 104 - 24 * 12 mm

|

|

Baba Ghor beads?

How much wear and tear will carnelian beads have

after 500 years? My guess is that the beads above are

older than the Cambey Ghor period. The 6 beads below are

in my opinion more in sync with not thousands, but

hundreds of years of human time ravage.

|

|

|

|

CARN 105 - 24 * 10 mm

|

CARN 106 - 19 * 8 mm |

|

|

|

CARN 107 -

25 * 11 mm

|

CARN 108 - 30 * 13 mm |

|

|

|

CARN 109 - 23 * 10 mm

|

CARN 110 - 30 * 9 mm |

|

|

|

|

|

INDIAN SARD BEADS

Sard is like carnelian a variety of chalcedony. It is

however harder with 7 on the Mohr scale, whereas carnelian

centers around 6,5. Sard is as you can see below brownish yellow

in color.

|

|

Click on picture for larger version

|

30 * 30 * 11 mm |

|

CARN - 111

Translucent sard bead from India. The shine in this bead is

very special.

Unfortunately the photo is not able to reflect it.

|

|

|

|

CARN 112 -

|

|

|