SULEMANI

& or BABAGORIA

BEADS

"Sulemani"

is a contemporary Indian term that pertains to black

onyx or black/brownish agate that has one or more white

stripes. This classification of beads, known as Sulemani

beads, is influenced by the presence of Islamic culture

in India since the 12th Century. Muslims, particularly

the Sufis, held a preference for this variety of beads,

characterized by one or more white stripes, for their

prayer chains. However, they were repurposing beads that

originated from a much older and different culture.

Many, although not all, of the beads showcased here come

from central India. World-renowned bead expert Jamey

Allen proposes that a more accurate term for most of the

agate beads displayed here would be "Babagoria."

"Babagoria" is a term used by locals

living in proximity to the sites from where most of

these beads have been sourced in Central India. In their

dialect, "Goria" means bead, while "Baba" denotes a holy

man. Hence, these beads have been colloquially dubbed as

"holy man beads." For centuries, locals have gifted

these beads to holy men across both the Muslim Sufi and

Hindu traditions.

Interestingly, the ancient agate mines in Ratanpur,

Gujarat were known as Baba Ghori. The term "Babagoria"

is a reflection of the shared ancient cultural backdrop

in which all beads were perceived. They were relics,

amulets, and talismans adorned by holy men in a

bidirectional relationship: wearing them conferred

holiness upon the individual, while simultaneously, the

sanctity of the holy person who wore them blessed the

beads themselves.

In all likelihood, the term "Babagoria" was coined by

locals residing near the ancient manufacturing sites.

Their intention was likely to elevate the status of

burial beads to sainthood, thereby making them more

marketable as sacred objects. This wouldn't be the first

or last instance in history where tradespeople have

influenced the naming of commercially valuable objects.

The relatively modern term "Sulemani," as suggested by

Jamey Allen, likely emerged to establish an imaginative

connection to the famed ancient King Solomon

in order to hype the prices on the bead market. I tend

to see the Sulemani as a genuine sufi term. The term

"Sulemani" may have originated within the Sufi community

when they started incorporating these ancient beads into

their religious practices. The name could be a nod to

King Solomon, a figure revered in Islamic tradition for

his wisdom and fairness. His association with magic and

control over jinn or spirits in some Islamic narratives

may have further bolstered the beads' perceived

spiritual significance. The Sufi community's use of

these beads, and their possible role in coining the term

"Sulemani," underscores how cultural and religious

interchange can shape the understanding and naming of

historical artifacts.

The

term Sulemani

bead

was an Islamic renaming of

beads already in use

for magic, religious, and currency

purposes

for thousands

of years.

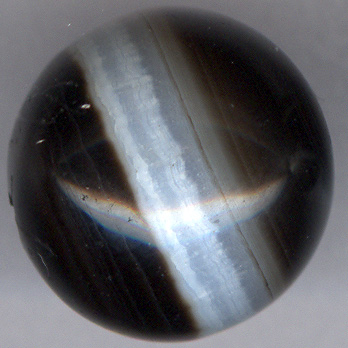

Black/brownish beads with white stripes

were used as objects of worship and in prayer malas by

the Buddhists of Asia

and most probably also before that,

reaching back to 700 B.C.

In the Buddhist context

ball-shaped beads, suitable for malas are named

Bhaisayaguru beads.

Just as with platforms like Spotify, where algorithms

habitually lean towards the most commonly used terms,

the label "Sulemani beads" has managed to dominate the

conversation. In the realm of contemporary global bead

communities, the term "Babagoria" remains largely

unfamiliar. Thus, for the sake of broad recognition and

understanding, we will continue using the term "Sulemani."

This highlights the evolution and adoption of popular

terminology over more localized or original names in a

globally connected world.

|

The beads in

my collection

are now for sale

Inquire

through bead ID

for price

Go2

boxes to

buy from

Click

on the

box

|

|

|

SM 1a -

average size 9mm -

'cooked'

Click on picture for a larger resolution

|

BEADS AS

CURRENCY

There's an intriguing saying in the

Konyak tribe: One bead necklace is equivalent to one

Nepali slave. This may seem strange to us today, but it

provides valuable insight into the role of beads in older

cultures.

Cultural customs and behavioral patterns within tribal societies

can often offer a unique window into our ancient past.

In the context of the Indus civilization, however, beads were

likely symbols of social status within an emerging labor and

class-based society, rather than units of currency. The idea of

using beads as money might seem natural today, but this concept

likely didn't exist in the early stages of history.

It's probable that only after the decline of the Indus

civilization did beads begin to evolve into a form of monetary

exchange. As trade expanded and societies grew more complex,

these small, portable, and universally valued items could have

found a new role in the economic systems of the time.

|

|

|

|

SM 1b - 5 to 6,5 mm - 'cooked'

Click on picture for a larger resolution

|

ATTRACTIVE, PORTABLE, AND RARE

The earliest forms of money needed to meet three essential

criteria: they had to be aesthetically pleasing, portable, and

difficult to procure or manufacture. This set of requirements

naturally led to items such as

shells

and beads being used as

mediums of exchange in increasingly organized and large-scale

trade systems. Hence, beads evolved from primarily being status

symbols to also serving the function of 'cash' in the burgeoning

urban trade economies of the Indo-Gangetic Plain during the

post-Indus period.

Beads, consequently, transitioned into Niksha, or circulating

money, akin to the later usage of

trade beads

in

Africa.

Interestingly, bead-currency was likely utilized within economic

systems even after the advent of the first

punch

marked coins

around the 6th century B.C. In a twist of historical irony,

history repeats itself: today, Sulemani and DZI beads are used

in facilitating transactions within China's parallel black and

gray economies.

|

|

|

|

SM 1c -

4 to 8 mm - 'over cooked'

Click on picture for a larger resolution

|

THE UNIFORMITY OF MONEY BEADS

The reason for discussing the concept of beads as money

in the context of Indus beads, despite them not being used as

such, is to draw attention to a significant transformation in

the role and characteristics of beads:

When beads transitioned into serving as a medium of exchange or

money, they lost their distinctiveness.

In other words, as beads began to be standardized for their new

economic role, their individual artistic expressions and unique

features became less important, if not undesirable. The emphasis

shifted from the artistic and cultural value of each bead to its

uniformity and reproducibility, crucial attributes for any form

of currency. This metamorphosis marked a stark departure from

the array of shapes, colors, and materials that defined the

Indus beads and their individualistic appeal.

|

|

|

|

SM 1d -

5 to 8 mm - 'over cooked'

Click on picture for a larger resolution

|

THE EVOLUTION TOWARDS UNIFORMITY

A critical requirement for a bead to evolve into a currency was

its ability to be recognized and valued over larger geographical

areas, necessitating a certain level of standardization. The

bead had to morph from a symbol of unique artistic expression

and rarity into an item of reproducible and recognizable

uniformity, akin to shells.

As these new requirements took precedence, the emphasis on

beauty, rarity, and diversity inherent in bead production had to

be down-prioritized. The aesthetics and individuality that

characterized the Indus beads gave way to an emphasis on

replicability and standardization.

This shift likely serves as the primary explanation for the

striking transition from the extraordinary variety and

uniqueness of beads seen in the Indus period to the relatively

uniform, mass-produced beads that emerged later. This

transformation marked a significant turning point in the role of

beads in society, from a symbol of personal status and cultural

expression to a utilitarian tool for economic transactions.

|

|

|

|

SM 1e

- 4 to 7,5 mm - 'over cooked'

Click on picture for a larger resolution

|

The prolific presence of beads, particularly from around 700

B.C. and the subsequent 1000 years, can be attributed to their

adoption as a form of currency. Despite the estimated 90% of

'ancient' beads in today's market being inauthentic, the

remaining 10% constitute a staggering number, hinting at the

scale of bead production in ancient times. In fact,

archaeological excavations occasionally unearth massive

quantities of ancient beads in a single find, sometimes

amounting to as much as 50 kg. This is analogous to the mass

production of automobiles by Ford in the 1930s, where the demand

for a ubiquitous commodity led to a substantial increase in

standardized, look-alike products.

|

|

|

|

SM 1f

- 5 to 7 mm - 'over cooked'

Click on picture for a larger resolution

|

|

Click on

the box

|

|

|

SM 2a

Click on picture for a larger resolution

SM 2a

Click on picture for a larger resolution

|

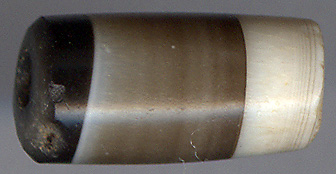

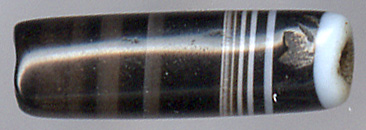

SULEMANI AGATE

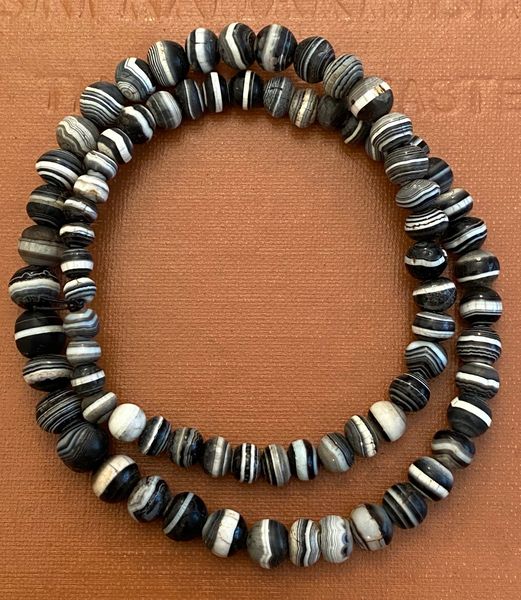

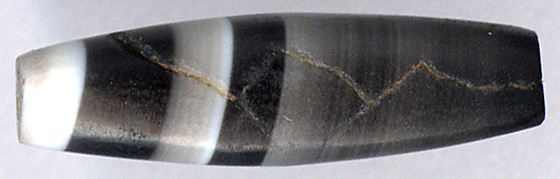

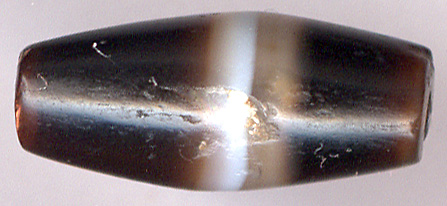

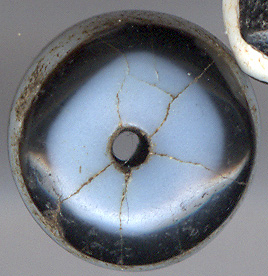

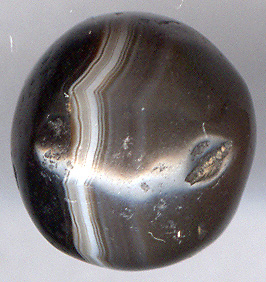

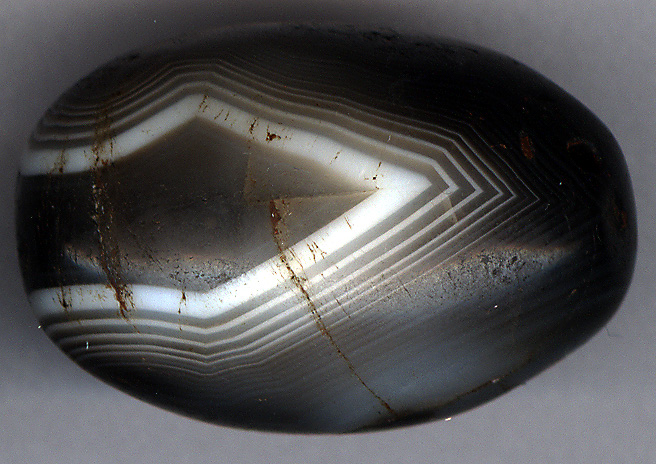

Displayed in illustration 1, 2, 3 & 4 you can observe

variations of typical Sulemani

agate beads.

Note the blank shining surface of these

beads.

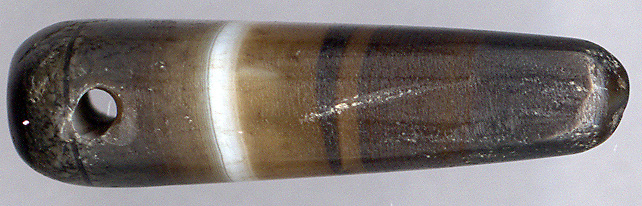

Cylinder shaped Sulemani

Onyx

beads

Onyx is virtually black agate

which is two-layered. In the case of sulemani beads the

layers are primarily consisting of black/brownish and

white.

|

|

|

|

SM 3 - 17 * 11 mm |

|

SM 4 - 14 * 9 mm

|

|

SM 5 - 23 * 10 mm

Illustration 3

|

|

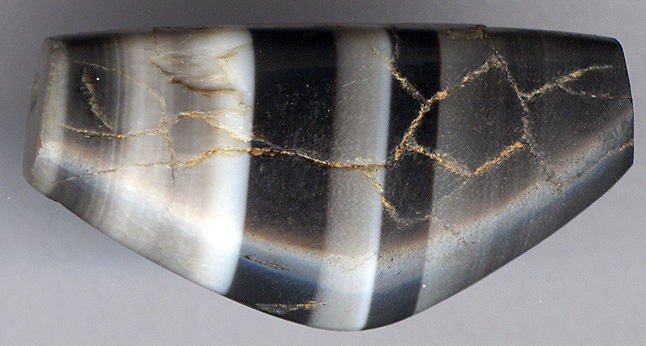

Truncated Convex Bicone Sulemani Onyx

Beads

|

|

|

|

Illustration 4

SM 6 -

22 * 14 mm

SM 7 - 23 * 13 mm

SM 8 - 23 * 12 mm

SM 9 - 15 * 10 mm

Pendant sulemani

SM 10 - 18 * 11 mm |

AGATE HEATED BY FIRE

Displayed in the illustrations 5,6 & 7 you will see a

different kind of black and white banded agate than the

beads shown above. The patina of these two kinds of

agate is quite different.

|

|

|

|

|

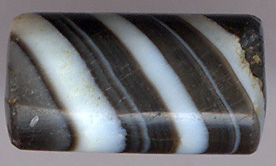

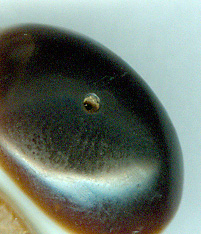

The difference in

patina

In illustration 5 the beads do not display the same kind

of glass-like shine as the beads in illustration 1, 2, 3

& 4. They have a more dusty, not reflective surface.

Greater contrast lines

Another characteristic is that the beads displayed in

illustration 5 show greater contrast between the black,

gray and white colors.

Black lines in white stone - not white lines in black

stone

Often the presence of white colored stone is, as you can

observe in illustration 6 dominating in this type of

agate:

|

|

|

|

Illustration 6

SM 22 - 19 * 7,5 * 4 mm |

One could as a general rule say that the typical

Sulemani beads as displayed in illustration 1, 2,

3 &

4 have

stripes of

white

in a black

stone where this other kind of

beads displayed in illustration 4 & 5

have black stripes

in

white

agate.

50 shades of gray

It is also worth to note that this type of agate stone

often displays distinct bands of gray

color

in many shades:

|

|

|

Illustration 7

SM 23 - 22 * 6 * 5 mm

SM 24 - 25,5 * 18 * 5 mm

A wonderful bow bead. Note the

distinct

black, gray and white color bands.

These beads were sourced from Burma.

They learned together with the spread of

Buddhism to manufacture these beads. |

The

absence of brown colors

Furthermore, this agate does not display brown or

brownish colors as you will often observe in the more

common Sulemani agate beads. An example of this brownish

color can be observed in these typical

Sulemani/babagoria beads:

CHANGE THROUGH

HEAT TREATMENT

The difference between the

'normal' Sulemani beads and these more white, gray and

black beads is due to differences in the heat treatment

process. These beads have been either deliberately or by

accident been put in fire making them more

white-black-grayish. The change might also be caused by

the heat from a funeral pyre.

Great art through fire!

Whatever the reason... seen from an artistic viewpoint I

love the appearance of these beads much more than the

more ordinary ones with their brownish colors as you can

observe above.

That leads me to the last theory, a theory I believe is

closest to the truth: These beads have been deliberately

produced to look like they do. They are simply too

beautiful to be a coincidental side product of a burial

pyre. According to Mr. Malik Hakila, a world leading

bead expert and a bead shop owner from Kathmandu who

also runs a bead factory in Cambay, Gujarat, there were

two separate ancient bead cooking techniques involving

in producing these Central Indian beads.

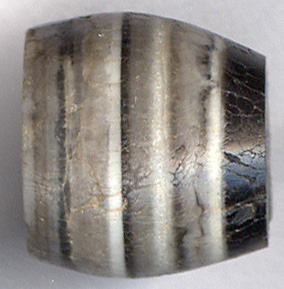

1) Ancient dry cooking by high temperature

The oldest technique, as one can observe in

illustration 5 to 8, was to heat-treat the beads

without oil, like the ancient Indians did with

carnelian, but with a much higher temperature. In this

way, the beads became non-translucent and with intense

jet black and powerful white bandings, which is an

advantage seen from an artistic viewpoint. The problem

with this technique is that it weakens the stone so

badly that it easily breaks. Even in the finished

specimen, one can find a lot of scars and cracks, as you

can observe in illustration 7. Scars and cracks

can happen anytime with this type of beads. I even had

some specimen that cracked right in my hand.

|

Click on picture for larger version

|

Vulnerable beads

In central India, there are ancient sites with

huge piles, almost ton's of ancient broken beads

made with the old and dry heating method. The

massive presence of this type of beads in a

broken condition indicates the problem with the

fragility of beads made by the old production

method.

A lot of these beads simply did not survive the

manufacturing process itself.

On the illustration, you can observe beads taken

from such a junk pile close to the bead

manufacturing place. Here we can observe beads,

broken before and after getting polished and

some broken during the tumbling process itself

as with the bead in the upper right corner with

a polished bead crack surface.

|

2) A more modern oil cooking

technique

The other and more modern, but still ancient technique

would be to cook the beads in oil. This technique keeps

the natural transparent parts of the agate and at the

same time upholds the strength of the bead. This method

replaced the former one about 2300 years ago. However,

the two techniques have most probably run parallel for

quite some time, depending on customer demand.

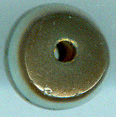

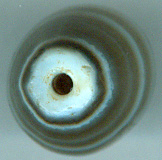

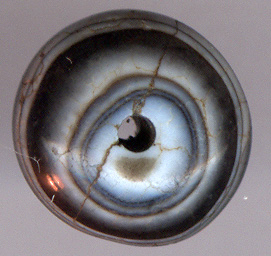

Larger & older holes in the dry & hot cooked beads

The holes are as you can observe in illustration 5 to

8 and mostly much larger in the dry & hot cooked

beads than in the more common agate bead in this

traditional oil cooked bead:

The generally larger holes in the dry & hot cooked beads

support the theory of two distinctly different ways of

bead treatment with radical different appearances.

Larger variation in motives in dry & hot cooked beads

Displayed in Illustration 8 one can observe the

presence of ultra swirling and abrupt geometric motives

and multiple eye formations in the dry cooked and

super-heated older type of beads. Swirling circular

motives are typical for normal agate, but even more so

in these specimens. It seems the different layers in the

agate chosen for dry & hot treatment are more irregular

and hence more interesting. Therefore my next hypothesis

is: In order to get the best art beads out of the

swirling effects of the agate, the the beads with most

interesting patterns and swirls were chosen for the old

heat treatment technique and the one with more regular

banding were chosen for the new technique.

The most wonderful artful swirling play of circles is

displayed in illustration 8

below, but can also clearly be observed in

illustration 5.

|

|

|

|

|

THE

USE OF OIL COOKED BEADS AS CURRENCY

For every over-cooked more ancient bead there are

hundreds of oil cooked beads.

Is it a coincidence that oil cooked beads

in mass production appeared on the historic Indian scene

at the same time as the rise of the use of money,

nishka? I don't think so. The oil-cooked beads

fulfilled the need of currency before the minted coins

took hold. For a long time, bead-coins and metal coins

most probably have coexisted. In this process of

monetization of beads, the production of the over-cooked

beads had to make way for the oil-cooked one out of two

simple reasons.

Oil-cooked beads were more durable and were not likely

to break when shifting hands in circulation.

Oil-cooked beads were less individual and artistic. When

cooked in oil the beads tend more to look like each

other, which is an advantage when used as currency.

With the rise of urban trade, artistic beads had to give

way to the more consistent mass production of

bead-currency.

THE TALISMANIC POWER OF THE ANCIENT DRY & HOT COOKED

BEADS

In a way, all ancient

beads are amulets - if one think they are. The

'amuletic' power of a bead can never be isolated from

the particular belief system in which the owner of the

bead orients himself. In my view the world is

constructed out of collective minds accepting the same

story told reality. The naming of beads is part of the

same game. Should we call these beads Sulemani,

Bhaisayaguru or Babagoria beads? Each name attracts a

certain collective reality, and these 'realities' will

fight internally about who is the most real reality.

Beauty is my religion

My belief system is centered around beauty

- not beautiful beauty, not a perfect beauty, but

transcendent beauty hidden in the perfection of the

imperfect. I would call it the sublime.

Imperfect, fragile bead amulets like these ancient over

cooked beads are full of story telling like faces of old

men and women. Therefore I call these beads sublime, and

that is why I wrote a

praise to the scarred bead.

To see the world as a story told reality or maybe even

fantasy is in fact very close to the ancient Indian

philosophy and according to my observations exactly the

part of Indian religious culture that originated, not

from the Arian invasion, but from India's own ancient

super culture: the Indus culture.

Where we in the West tend to describe all mind made

realities as unreal in opposition to

positivistic science, the ancient Indian thinking is one

step ahead in pointing out - long time before the

quantum physicists - that the observer is actually

creating the observed.

Therefore beads have the power you observe them with.

But why ancient beads? Why not something plastic

fantastic?

Exoplanetarian beauties

When I look at these worn and torn ancient dry &hot

cooked beads - sometimes looking like exoplanets from

far away solar systems - I am taken by awe. They are the

eye bead displayed above full of fragile cracks emitting

ancient light. Their swirling unpredictability makes

them perfect as amulets setting the course for my own

unknown future.

The typical Asian collectors would not like them due to

their imperfections.

I however, observe this imperfection as perfectly

imperfect.

An ancient bead is due to its history and aesthetic

appearance an ideal focus point for meditative

concentration of the powers of and in the mind. The

scars, marks, and cracks are ancient signatures of time

itself.

It is an ideal hub where the Soul and the zero can meet,

but not in the ideal formlessness of the zero alone.

Because by accepting the scar as beautiful, you accept

the imperfect life you live as beautiful. No need of

escaping into the perfect, but depersonalized space of

the zero.

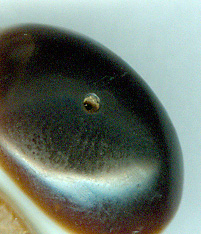

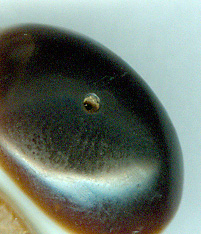

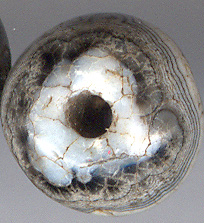

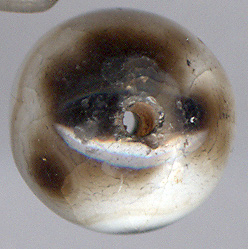

THE (W)HOLE IN THE EYE

- THE ZERO AND THE SOUL

The wonderful ancient big holed ball

beads displayed here illustrates the ancient bead makers

preference to put the hole as far as possible in the

center of the eye.

The reasons for placing the hole in the eye could

be

several. One is most probably religious and symbolic.

The other could be purely out of

aesthetic reasons.

It is worth noting that the hole in a bead also

resembles a zero. This is particularly interesting

because it was the Indians who invented the zero. The

Hindi name for zero is still today the word shoonyo,

an old Buddhist word for the fundamental perfect

emptiness of existence.

|

|

|

|

Illustration 9 |

SM 32 - 14,5 * 11

|

SM 33 -

15 * 12 mm (Afghanistan)

- Sold |

SM 34 - 11,5 * 10 mm

|

SM 35 - 10 * 8,5 mm |

SM 36 - 11,5 * 11 mm |

SM 37 - 9 * 7 mm |

SM 38 -

10 *

9,5 mm -Sold |

SM 39 - 10 * 8,5 mm |

SM 40 - 9 * 7,5 mm |

SM 41 - 9 * 7,5 mm -Sold |

SM 42 - 8 * 6,5 mm |

SM 43 - 7,5 * 6,5 mm -Sold

|

SM 44 - 6 * 5 mm -Sold

|

SM 45 - 6,5 * 5,5 mm |

SM 46 - 7,5 * 5,5 mm -Sold

|

SM 47 - 6 * 5 mm

|

|

|

Below you can observe a few beads with holes drilled

with apparently no considerations to the eye patterns.

The reasons for this could be several. Mainly I think it

is due to technicalities, in the sense that the very

nature of the stone could demand the hole to be drilled

in a

particular

place.

The hole could also be put

as you can observe in the beads below out of other

aesthetic motivations. The reason could also be due to a

bead makers ignorance or not caring about symbolic eyes.

There were countless centers for bead making in India -

both seen in a historical and geographical view.

Most probably these centers had different cultural

and religious views. As there always in ancient India

were many different gods and religions there must also

have been a lot of difference in the context of

mindsets.

So it is possible that we had centers of bead making

where the bead makers did not care about symbolic eyes

and holes. It is here worth to remember that India had a

great time of skepticism and atheism already 100 years

before the birth of the Buddha.

|

|

|

|

|

NEW HOLES IN OLD BEADSThis ancient bead

displayed below has no hole.

It never made it the whole way to the end of the manufacturing

process. It is not uncommon to find such

beads.

The wonderful beads SM 53,54 and 55

just below are ancient. However,

they were found without hole. So the finders of the beads

drilled new holes in them. Unfortunately,

my scanner is somehow not able to catch the true translucent

beauty of these beads.

|

|

|

SM 53 - 11 mm - a bead whithout hole

SM 54 - 15 mm

SM 55 - 14 mm

SM 56 - 13,5 mm

|

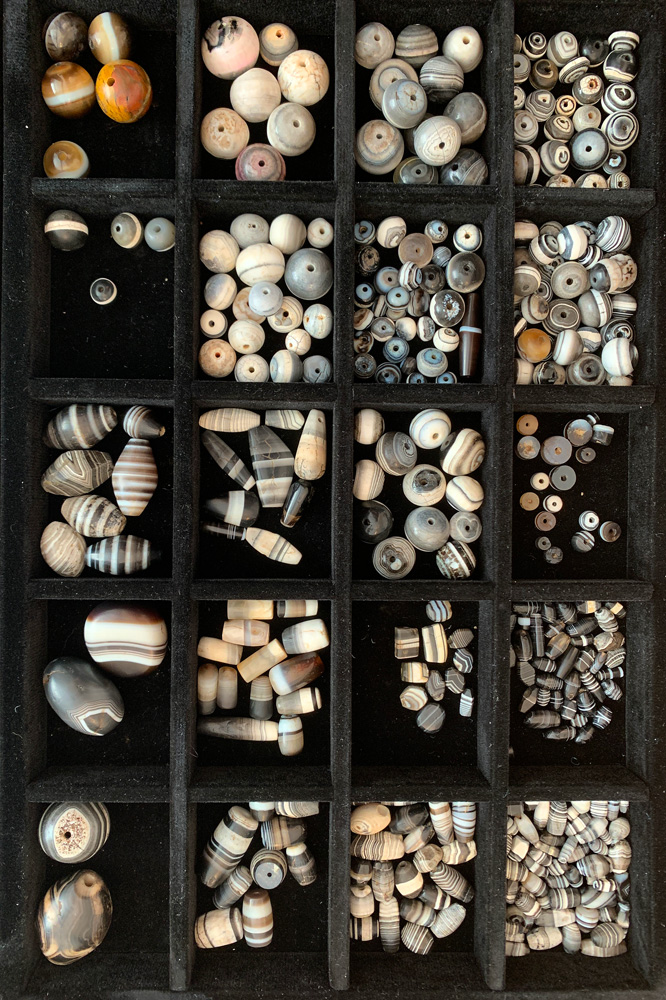

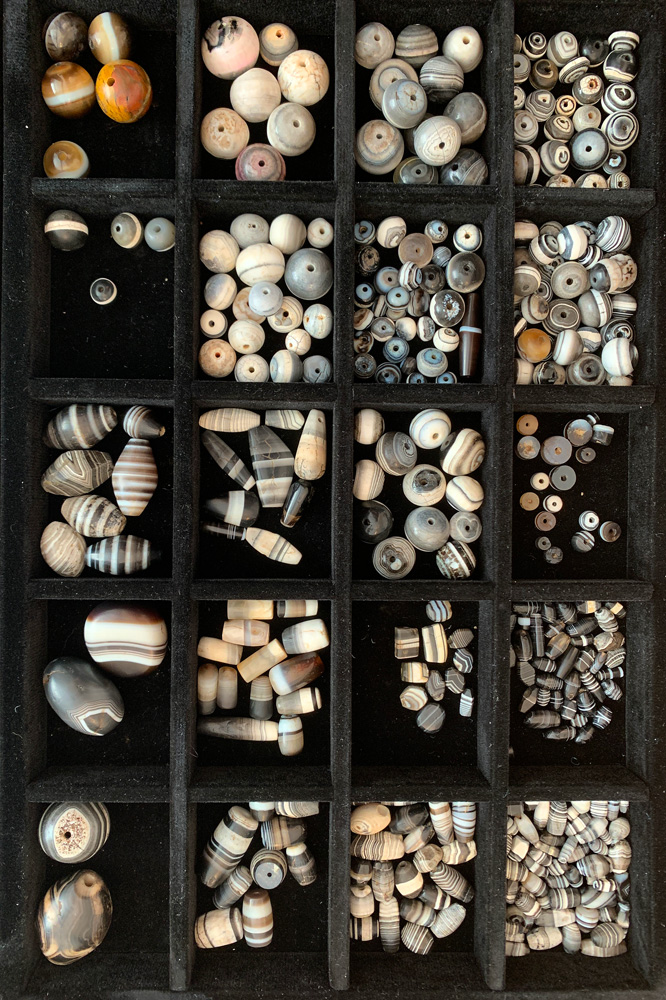

BABAGORIA

BEADS IN VARIOUS DESIGNS

In the following section you can, if you

like, try to see the difference between the two kinds of

agate.

Since I

hunt the

older dry & hot cooked

agate

beads, most of the beads

displayed below

belong to that category.

|

|

|

|

SM 57 - 18 * 7 * 6 mm

SM 58 - 17 * 8,5 * 7 mm

SM 59 -

12 * 7

mm

|

SM 60 -

12 *

6,5 mm

|

SM 61 - 12 * 8 mm |

SM 62 - 9 * 7 * 6 mm

|

SM 63 - 11 * 6,5 mm |

SM 64 - 12,5 * 7 mm |

SM 65 -

|

SM 66 - 11,5 * 6 mm

|

SM 67 - 14 * 7 mm

|

SM 68 - 12 * 7,5 mm

|

SM 69 -

10,5 * 5 mm

|

SM 70 - 9,5 * 7 mm

|

SM 71 - 13 * 6 mm

|

SM 72 - 9 * 5 mm |

SM 73 - 12 * 6 mm

|

SM 74 - 15 * 6 mm |

SM 75 - 14 * 4 mm

|

SM 76 - 12,5 * 7 mm |

SM 77 - 9 * 7,5 mm

|

SM 78 - 10 * 7 mm |

SM 79 - 9 * 5 mm

|

SM 80 - 9 * 5,5 mm |

SM 81 - 9 * 7 mm |

SM 82 - 8 * 6 mm |

SM 83 - 9 * 8 mm |

SM 84 - 8 * 7 mm

|

SM 85 - 11 * 6 * 4 mm |

SM 86 - 9 * 7 * 4,5 mm

|

SM 87 - 14 * 8 mm

Note the very rare blues stripe |

SM 88 -

11 * 7 mm

|

SM 89 - 12 * 5,5 mm |

SM 90 -

11 * 5 mm

|

SM 91 - 9 * 5 mm |

SM 92 -

9 * 6 mm

|

SM 93 -

8,5 * 5,5 mm

|

SM 94 - 8,5 * 5 * 4 mm |

SM 95 - 9 * 6 mm

|

SM 96 -

8 * 5 mm

|

SM 97 - 11 * 8,5 * 6 mm |

SM 98 - 10 * 6,5 mm

|

SM 99 - 8 * 6,5 mm |

SM 100 - |

SM 101 - 10 * 11 mm

SM 102 - 5 * 8 mm |

SM 103 - 5 * 6 *

5,5 mm

SM 104 -

25 * 7 mm

SM 105 - 17,5 * 7 mm

SM 106 -

18,5 * 12 mm

SM 107 -

17 * 6,5 mm

SM 108 - 16 * 7 mm

|

BALL BEADS

|

SM 109 - 6 * 5 mm |

SM 110 - 6 * 6,5 mm |

SM 111 - 7 * 6 mm |

SM 112 - 7,5 * 6,5 mm |

SM 113 - 7 * 6,5 mm |

SM 114 - 7 mm |

SM 115 - 7 * 6 mm |

SM 116 - 7 * 6 mm |

SM 117 - 7 mm |

SM 118 - 7 * 5 mm |

SM 119 - 8 mm |

SM 120 - 8 mm -Sold |

SM 121 - 8 * 7 mm |

SM 122 - 8 mm |

SM 123 - 8 * 7 mm |

SM 124 - 8 * 7 mm |

SM 125 - 9 * 7,5 mm |

SM 126 - 9 * 6,5 mm |

| |

|

|

SM 127 - 9 * 7 mm -Sold

|

SM 128 - 9 * 6,5 mm

|

SM 129 - 9,5, * 8,5 mm

|

SM 130 - 9 * 10 mm

|

SM 131 - 10 * 7 mm -Sold

|

SM 132 - 10 * 9,5 mm |

SM 133 - 10 * 12 mm -Sold

|

SM 134 - 10 * 6,5 mm -Sold

|

SM 135 - 10 * 10,5 mm

|

SM 136(1) - 11 * 9 mm -Sold |

SM 137 - 11,5, * 7,5 mm

|

SM 138 - 11 * 7 mm |

SM 139 -

11 * 10,5 mm

|

| |

|

SM 140 -

14 mm

SM 141 -

14 * 12 mm

Ancient bead with a new hole

|

This wonderful flat oval tabular, natural banded

Sulemani agate bead displayed blow has a beautiful

patina and a unique pattern. This bead has been

heat treated with honey or sugar.

|

|

|

SM 185 -

26 * 23 * 12 mm

Origin: The Himalayas

Period: 300 B.C. to 1000 A.D.

|

|

|

|

SM 186 -

27 * 18 mm

|

Sulemani pendant beads

|

|

SM 187 -

22 * 9,5 mm

SM 188 -

15 * 8 mm

SM 189 -

21 * 9 * 7 mm

SM 190 -

11,5 * 9 mm

SM 191 -

14 * 9 mm

|

Buddhist Bhaisajyaguru beads

Sulemani agate was as mentioned in the beginning used by Sufi

Moslem Faqirs and before that, they were used as Buddhist prayer

beads. Especially Afghanistan is interesting in this context.

Afghanistan was a predominantly Buddhist culture up to 1000 AD!

The ball shaped Sulemani beads are

also known as Bhaisajyaguru beads.

These Prayer beads remove according to the Tibetan tradition,

roots of diseases, ensures health and longevity.

In

Mahayana Buddhism,

Bhaisajyaguru represents the

healing aspect of the historical Buddha Sakyamuni. These beads

have been in the hands of beings with pure intentions for

generations. Some of these beings may even have been

enlightened!

|

|

Here you can see the wonderful Bhaisajyaguru eye bead from

Afghanistan that is displayed on the top of the page

Bead Magic. It really shows that

the bead hole itself actually can serve as a Magic Eye!

|

SM 0 - 14 * 14 mm

|

And here

are some boxes to buy from:

Note the peculiar bluish light in these rare specimens

SULEMANIBOX 1

Click on boxes for larger picture

SULEMANIBOX 2

SULEMANIBOX 3

SULEMANIBOX 4

SULEMANIBOX 5

|